Last year we covered an educational initiative in Brazil, by Bayer-owned intimate health brand Canesten. The Intensivão Da PPK (Vagina Academy) campaign was a TikTok-based ‘school’ created by agency AnalogFolk, London, to educate Brazilian women on vaginal and vulval health.

Inspired by the alarming statistic that one in four Brazilian women is ashamed to even say the word ‘vagina’, the idea was conceived under Canesten’s global brand purpose, ‘To help young people to set themselves free from shame and discomfort.’

Following the success of this pilot campaign (The Intensivão Da PPK TikTok channel received 44 million video views), the brand has launched similar initiatives in Italy and Australia, and now in the UK.

The Truth, Undressed is a global education at scale platform to teach young people about vulval anatomy and vaginal health, covering everything from health conditions to pubic hair, all free of euphemism, metaphor and sexualisation.

The platform was inspired by the fact that, though more progressive in terms of attitudes towards intimate health, the UK’s knowledge and access to education is still ‘abysmally low’.

According to Canesten, 60% of women in the UK only found out about vaginal infections when they first experienced one and 68% of young women wished they had learnt about vaginal discharge as a primary indicator of health. Further, 81% of young women agreed that there should be better vaginal/vulva education in schools.

The platform launched with a website, as images of real vulvas are blocked on social media sites. AnalogFolk developed social video ads to drive traffic to TruthUndressed.co.uk and also partnered with educational body the PSHE Association (Personal, social, health and economic) Education to create a set of lesson plans for use in secondary schools.

Results Updated 10/10/22: According to the agency, Vagina Academy lesson plans have been taught to 150,000 students as part of the National Curriculum in schools across the UK. The campaign reached 3.4 million people via the social media element.

Update 7/12/22: More than 163 million people were reached through global media coverage and in one month there were 42,000 visits to the website, with 81,290 website visits to date.

We spoke to AnalogFolk senior creatives Gracie Hawes and Jacqueline Hedge, creative director, Amandine Fabian, and head of brand strategy, Alisa Maul, to find out what the challenges were of adapting this pilot campaign for a new market, how they approached the creative, and what the long-term goals are for The Truth, Undressed. They told us:

To have true impact and drive early education, infiltrating the curriculum was a key part of this campaign

Although the UK is a more liberal than Brazil, the country has some way to go in terms of realistic representation of vulvas and vaginas

The co-creators on the programme were selected for their expertise in capturing realistic, honest imagery of nude bodies

The choice of creative was influenced by UK advertising restrictions as well as the nature of the content

What is Canesten’s key business challenge in the UK?

Alisa Maul: People only ever interact with Canesten when they have a problem, and they need a quick fix to treat a vaginal health issue which means they have no real emotional connection to the brand. While Canesten is seen as effective and fast acting, the relationship with the brand is short-term and purely functional.

Canesten needs to establish a long-term emotional relationship where the brand can add meaningful value to consumer's lives which is why there was the need to put purpose at the heart of what Canesten does as a brand. Canesten’s purpose is to help people set themselves free from shame and discomfort.’

Our educational programme The Truth Undressed aims to deliver on this purpose by creating conversation-starting, shame-free education that stops speculation and sheds light on what really happens in the average pair of pants.

Where does the brand sit in the market?

Maul: Canesten is the market leader in the UK when it comes to treating vaginal infections like thrush and bacterial vaginosis. This means people do not have a long-term relationship with the brand but only ever interact with it a few times in their life.

Moreover, new market entrants who focus their offering on ecommerce have entered the market which meant Canesten was under increasing pressure and had to demonstrate category leadership when it comes to the topic of vaginal health.

We wanted to do this by focusing on a brand purpose led approach which would enable Canesten to add value to consumers lives by focusing on more than just treatment. 60% of UK women find out about vaginal infections when they first experience them and instead of continuing to talk to people when they already experience a vaginal health problem, we wanted to help consumers understand how to prevent infections before they even occur.

To do this we focused on the next generation of first-time sufferers who are in need of education and factual information when it comes to vaginal health.

Gracie Hawes, AnalogFolk

What are the key ways in which this UK campaign differs from the Brazil pilot?

Gracie Hawes: The biggest thing is probably the market in terms of the level of maturity, in terms of shame – Brazil is obviously a traditionally Catholic country.

The UK is slightly more liberal, although the problem of a lack of education and shame is still rife - 60% of UK women find out about vaginal infections when they first experience them, and 81% of young women (18-24) agreed that there should be greater education about vulvas in schools - and Canesten had already done a project to reduce stigma called ‘Different is Normal’ with sexual health charity Brook.

So we needed to build upon the steps they’d already made with something that took the conversation further, and not just provide an education, but one that lets you see reality for the first time (outside of porn). And by not just creating a campaign but tackling the UK education system with lesson plans for schools, too.

Alisa Maul, AnalogFolk

In Brazil, you can work with influencers, but in the UK, pharmaceutical brands are not allowed to work with influencers. So that was a big difference. And because of the nature of the content and wanting to show reality, the bulk of the work couldn’t live on social, either. So instead of, being a TikTok or Instagram campaign, it predominantly lives on our microsite, truthundressed.co.uk.

We’re also working with schools, which goes back to that idea of needing to push the conversation slightly further for the UK and wanting to impact the actual education system. We have a set of lesson plans that teachers can download and teach for year seven to 13, too.

Then there are smaller differences in terms of making the actual content culturally relevant. In Brazil, we talked a lot about why you shouldn’t sit around in your wet swimsuit, and obviously, that’s less relevant for the UK. Another thing is that we talk about sex a little bit and its connection to infections more openly [in the UK].

What was the key insight behind The Truth, Undressed?

Maul: Shame stands in the way of good vaginal health. Due to shame associated with vaginal infections, consumers try to fill in their knowledge gaps by turning to the internet where misconceptions thrive. Myths that ‘thrush and BV are STI’s’ and have something promiscuous about them or that they can ‘be cured with yoghurt and garlic’. Information that is not only false but can also cause harm to vaginal health.

Jacqueline Hedge, AnalogFolk

We also noticed that the language differs: the Brazil pilot was gendered, while this campaign refers to ‘people with vaginas’.

Hawes: That was a learning from the first iteration about how we can be more inclusive. Not everyone with a vagina is a woman or was born female. After making the first one, it was about growing and learning and adapting the next one to be more inclusive. Even around the design direction, there are all sorts of aspects that we looked at to make it appeal to a broader range of people. And even if you don’t have a vagina, it’s really important that everyone learns and deals with the shame around this. We need people to be allies in terms of not perpetuating myths or shameful stigmas and speaking about it in a way that’s very open.

Jacqueline Hedge, AnalogFolk

What key research/findings informed the campaign?

Maul: Our global research demonstrated that shame persists across the world when it comes to vaginal health. In the UK particularly 60% of women felt guilty when having thrush and 2/3 of women between the ages of 18-24 are too embarrassed to say the word ‘vagina’ to their doctor while 66% of women in the UK aged 18 to 24 avoided going to the doctor to talk about gynaecological issues altogether.

Shame flourishes due to misinformation and Canesten’s primary research demonstrated the lack of education even more. A study of 1000 women in the UK revealed that only 6% of UK women find out about intimate health conditions through school and university education and that 68% of young women (18-24) wished they had learnt about vaginal discharge – a primary indicator for understanding the health of your vulva. In total 81% of young women (18-24) agreed that there should be greater education about vulvas in schools.

Talk us through the different elements of the campaign.

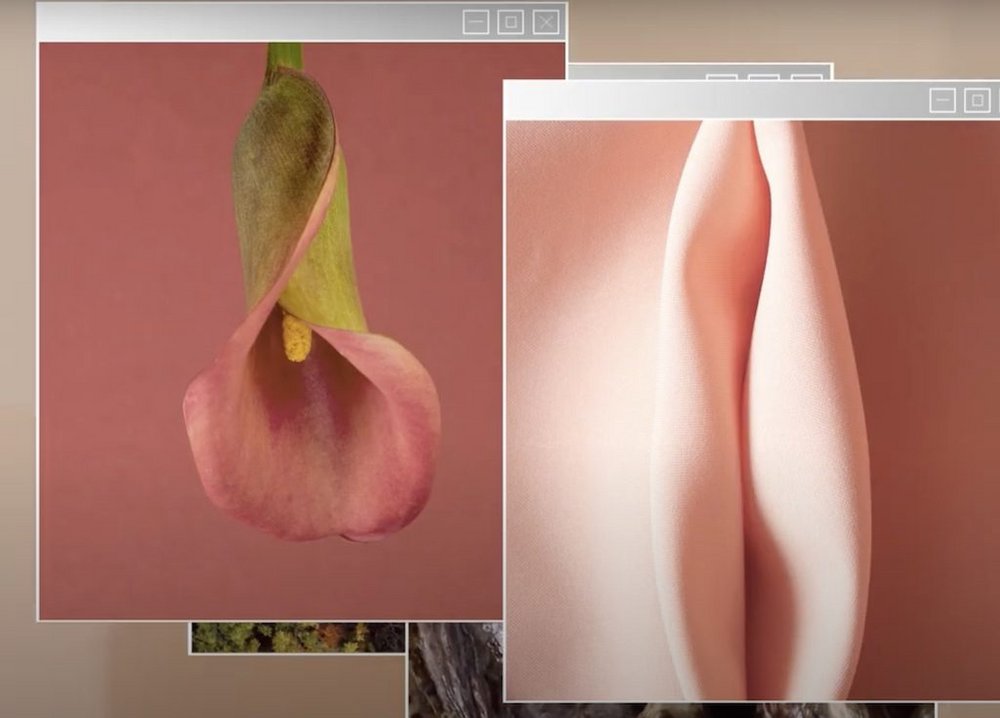

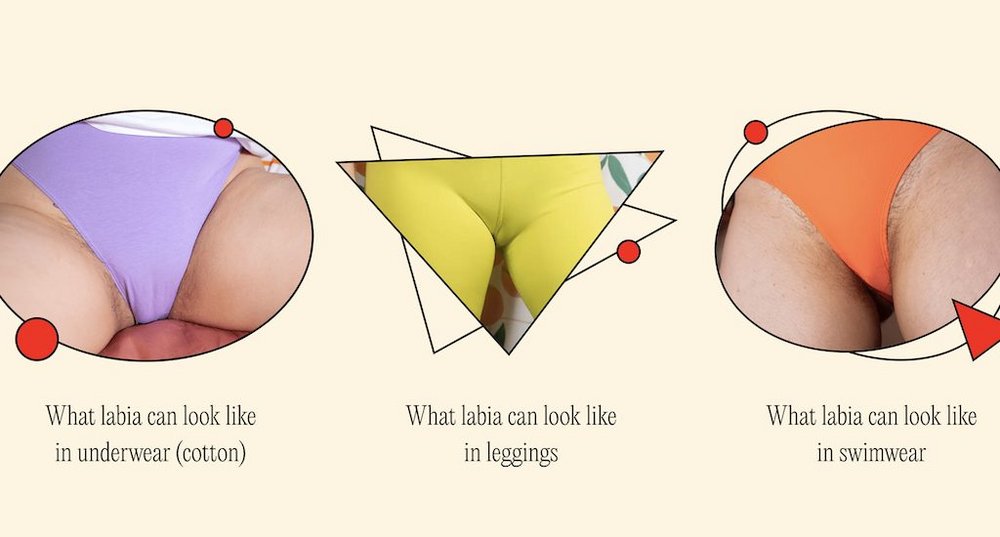

Jacqueline Hedge: As Gracie said, it couldn’t live on social media. But the choice of a website gave us an opportunity to cover quite a large range of topics within quite a small space. It housed all the information that we had across the 22 articles, with all the topics presented in various different ways. Where it was applicable, we used photography. The photography was never intended as something purely for shock factor, and it’s certainly not for entertainment or adornment, it’s always there for a reason.

For example, to show diversity of vulvas in the context of talking about labiaplasty and how you don’t need to be neat and tidy to be acceptable, or to show realistic representations of discharge. We really wanted to try and show reality because when you type in, say, ‘thrush discharge’ on Google, you either get very in-your-face medical pictures, which probably don't help when you’re looking at your pants, or descriptions that can be hard to decipher.

We wanted to represent what people would come across in their daily life and show a bit of normality of what it’s like to own a vulva and a vagina, bringing more of those visual elements, alongside the medical information that is in there as well. We also wanted to make sure that the tone of voice is friendly.

Jacqueline Hedge, AnalogFolk

We didn’t want to sound like a textbook, we would rather sound like an older sibling or a friend, rather than being preachy. We also wanted to make sure that it was inviting, something that people would want to seek out and spend time with of their own accord. And then to reflect our ambition to make sure that we’re creating meaningful and impactful change, we [partnered with] the PSHE Association [the UK’s national body for personal, social, health and economic education].

We were having all of these discussions around what we could do to actually make sure that we make a difference. And yes, creating a fame-generating campaign could do that. But we’d still only be existing in certain spaces and might end up preaching to the choir, depending on what corners of the internet we start popping up in.

So we landed on the fact that if we want to be making societal change, we needed to get this into the education system, because at the end of the day, that’s where everyone is learning about this stuff. It’s been taught in schools, generally, it’s been taken seriously. PSHE had recently been fighting to update the relationships and sex education curriculum, so they seemed like the perfect partner to give us the advice that we needed and make sure that our education content is as effective as it could be.

They were able to help us with the set of lesson plans, and they appraised them themselves. We had workshops with them to decide what subjects we needed to cover, and what things a young person would need to know about vulvas and vaginas, across all the different sexes – what is it that is going to help you understand your body or respect someone else’s body.

That was then tiered across the different age groups as well, to be age-appropriate. So the 11-year-olds in year seven are learning about anatomy, and the basics of discharge and some infections. Then it’s only when you get up to 16 and the legal age of consent that we start bringing sex into the conversation. And then we started talking about things like smell and taste, to reflects some of the issues that they might be facing.

The social ads that are driving [people] to the website were created off the back of the facts. So we still needed ads that reflected the problem back to people and encouraged them to come to the site, but also worked around the fact that we can’t show the actual content that we have on the website on social. That was an exercise in working out what was most grabbing and emotionally hooking to make people pay attention to this, whilst also trying to not play into the problems that we were trying to fix with this campaign.

Gracie Hawes, AnalogFolk

The images and language are noticeably stripped of sexualisation or euphemism. How did you approach the tone of the creative?

Hawes: Great attention has been given to ensure these images truly show what vulvas look like in a desexualised, educational context. For the photography, we worked with the content production company Untold Fable whose mission is to make diversity in front of and behind the camera the norm, and Sophie Mayanne, who shot the Mothercare Beautiful, isn’t she campaign. She’s also got a project called Behind the Scars where she captures people with scarring on their body and tells their story.

We selected Sophie for her realistic and natural style and her work on real representations of bodies. We also have portraits of people with a vagina, shot by Holly Wren, featuring women, trans-men and non-binary people.

[Sophie] felt like a really good fit. She has a lot of interest and appreciation for things that we might normally consider imperfections and reframing them and having more openness around them. In terms of making it feel very open and relatable and down-to-earth and not clinical or scary, we did a lot of work around how we were going to shoot the photos.

We coined this phrase ‘naturally nude situations’. So all of the vulvas were shot in scenarios like being in the bath, or getting out of the shower, or getting dressed after the shower – scenarios that were really far apart from anything sexual, just to remind ourselves that that’s not the only time that we’re naked, and it’s okay to look at our body parts for the purposes of education.

We did this whole audit of imagery, where we looked at stuff that felt a bit suggestive, and stuff that felt very confident and neutral, and then basically set ourselves some ground rules. One of them was about posing and making sure everyone felt open and comfortable and powerful. The lighting had to be neutral and daylight, with no suggestion of nighttime, and also very bright so you can see every detail.

We haven’t really seen anything like this ever before. You don’t see photos like this, that aren’t part of pornography or sex scenes in films. So we had to write our own rulebook in a way. Then, in terms of [photographing the discharge in] the knickers, that was about making it relatable. That is how it appears on a daily basis. And when you remove it from [the context of] your knickers it just becomes very cold and medical and instantly makes people feel a little bit uncomfortable. Like it’s something to be afraid of.

How did you cast your contributors, for both the testimonies and the photo gallery?

Hawes: For the photography, we had an intimacy coordinator for the shoot called Lydia Reeves. She is also an artist who makes casts of people's vulvas for an art project called the Vulva Diversity Project. She helped us find our cast: she went through all the people who had taken part in her artworks and then we approached them with a whole [set of] criteria for all of the different types of bodies that we wanted to portray on the website. From there, we managed to gather the perfect collection of different people of different identities and body types that could star in the photos, and everyone was super keen.

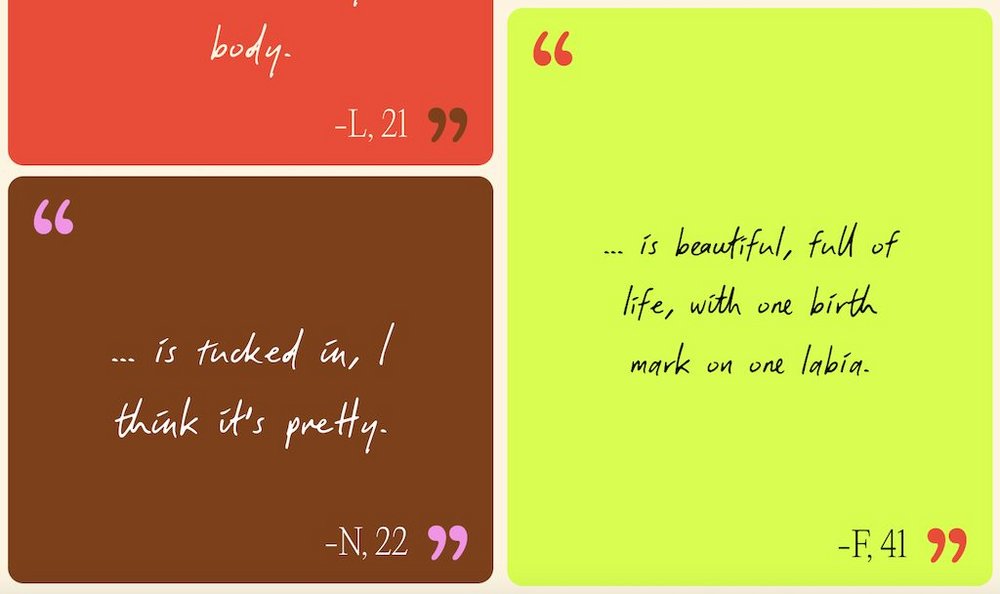

The quotes came from a public call for answers to questions about how people’s bodies look or their experiences. It covered so many different experiences and a lot of different topics. I’m really glad that those were included, they do provide a lot of richness for people to not just see, but to hear descriptions. Sometimes they’re a bit sad, sometimes they’re very positive, sometimes they make you laugh, there’s a real range of emotions.

Amandine, AnalogFolk

When did this actually launch? Have you had any sort of feedback yet?

Hedge: It launched on 18 July, the week schools broke up [for the holidays], so we’ll see how it lands in the next school year. It’s going to be quite a long-term thing to see the full effects of the lesson plans within education. But the site seems to have gone down really well.

We’ve had some predictably raised eyebrows from some people on Twitter, but for the most part, it seems to have landed quite well, without much backlash. PSHE did some testing of the lesson plans and we got full marks across the board, with students feeling engaged, the teachers feeling like the guidance was helpful, the content feeling necessary and impactful.

There were some comments from the teachers as well, saying that there might have been a few titters among the students, but eventually, once they get into it, they realised the importance of it, and the fact that they’re learning about themselves.

What’s the lifespan of this campaign? Do you think of it as an evergreen resource?

Amandine Fabian: Yeah, we’re already talking about the [second phase]. The primary objective was to educate, so of course it’s going to be long term. For us it’s never been just a small campaign. It’s more based on purpose. And it will take time to evolve and to normalise conversation, to break these taboos, until everyone realises that there's nothing to be ashamed of and that you can go and see your doctor and talk about vaginal health questions.

So it’s really important for us that there is a long term change to our mindset and how we represent people with vaginas in media, how we be more inclusive of everyone, how we portray vaginas more realistically. Even if it's just through an illustration, using different skin colours or different type of pubic hair or bodies, it’s really important, and it will take time.

Amandine Fabian, AnalogFolk

How does this campaign push the category forward?

Fabian: Campaigns like Viva la Vulva and Blood Normal paved the way, and we went a step further. Before the campaign, we did all this research about the lack of diversity and the lack of representation and how shame affects people’s relationships with their vaginal health. And through all this learning, we realised that we needed to have this visual representation, that's why we articulated everything through this photographic element.

It’s the first time that we’re showing vulvas and vaginas in a non-sexualised way. We tried to break the taboos, to show that there’s no normal vulva, there’s no particular shape. We should be more conscious as advertisers about what we show and who we include in a conversation, to show that everybody should be included in the conversation, no matter how you identify.

Hedge: Last year, we launched Canesten’s new brand purpose: ‘Help people set themselves free from shame and discomfort.’ Through our research, we’ve identified that shame and taboo come from a lack of discussion, and a lack of education. Therefore, to truly overcome shame and drive lasting, impactful access to vaginal health, we needed to work with schools – integrating the content of our platform to the mandatory school syllabus – and needed to develop an educational platform that focuses on eradicating shame and stigma through education at scale.

As Lynn Enright states in her book Vaginas: ‘Misinformation has consequences. When information is obscured, harmful myths fill the gaps and stigma flourishes.’ The more facts we know and share, the less space we have for rumours to prevail. And the more people learn the truth about vaginas, the less shame they will feel about their own body. Shame and misconceptions will continue to propagate until everyone is educated on vaginal health – not just people with vaginas – that’s why it’s so important to normalise talking about vaginas if we want to eradicate taboos.