How attention can save share of voice /

A new report by an Australian trade body asserts the importance of share of voice as a measurement tool in the age of splintering digital media and share of search

James Swift

/

Photo by Jason Rosewell on Unsplash

Attention metrics can save share of voice (SOV) from obsolescence in the age of digital media, according to a new report.

SOV is a measurement model that asserts brands grow when their share of a category’s total advertising spend exceeds their market share, and it has been used widely by marketers to plan budgets since the 1990s.

But digital media is making SOV more complicated and less reliable. For one, not all digital channels can be measured, which makes it harder (if not impossible) to accurately calculate total category advertising spend.

The arrival in 2020 of share of search as a potential successor metric has also put the future of SOV into question.

But a new report from Advertising Council Australia (ACA) argues SOV can and should survive.

‘The founding principle of SOV – the intensity of a brand’s advertising relative to its competitors – remains critical in planning the investment levels required to build and maintain the mental availability of brands,’ wrote Professor Karen Nelson-Field, who contributed to the report.

Nelson-Field has developed a new framework, called Attention Adjusted SOV, that brings SOV up to date by measuring attention.

Attention metrics cannot illuminate the dark corners of the internet where ad spend is hard to track, but Nelson-Field contends that they can improve SOV by more accurately measuring the value of impressions.

Digital media deliver wildly differing levels of user attention, which affects both long and short-term advertising impact. In particular, platforms with an interface that encourages users to frequently switch their attention between ads and other content fare more poorly, according to Nelson-Field. The strength of the creative work also plays a big part in how much attention an ad attracts, too.

As a result of the widening gulf between the price of an impression and the attention it delivers, SOV is untethering from SOM, wrote Nelson-Field. Using attention metrics to more accurately calculate the value of an impression paints a truer picture of share of voice, bringing it back in line with SOM.

‘Attention Adjusted SOV is new thinking, and will take some time to process, but dismissing the concept is like saying ‘let’s not use DNA testing in cold cases’ because it might change the outcome,’ wrote Nelson-Field.

The ACA report, called To ESOV and Beyond, was co-authored by Robert Brittain and Peter Field.

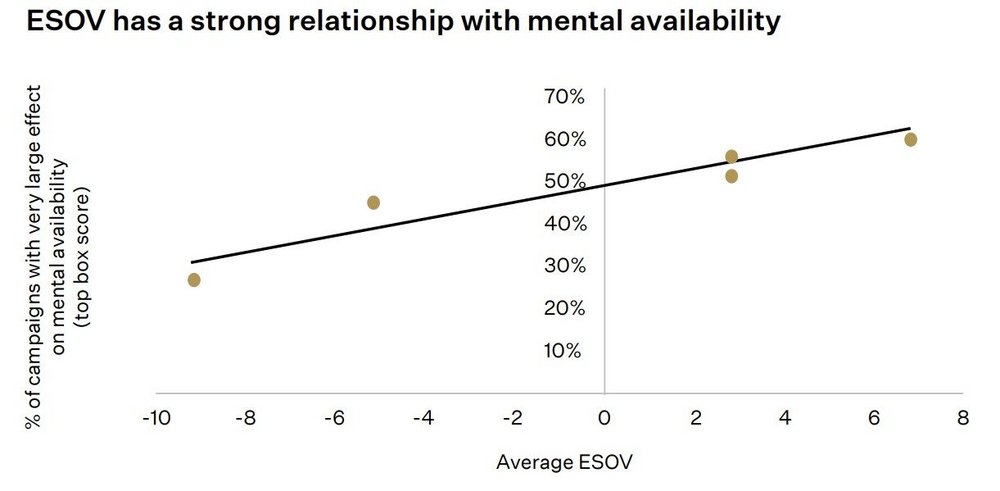

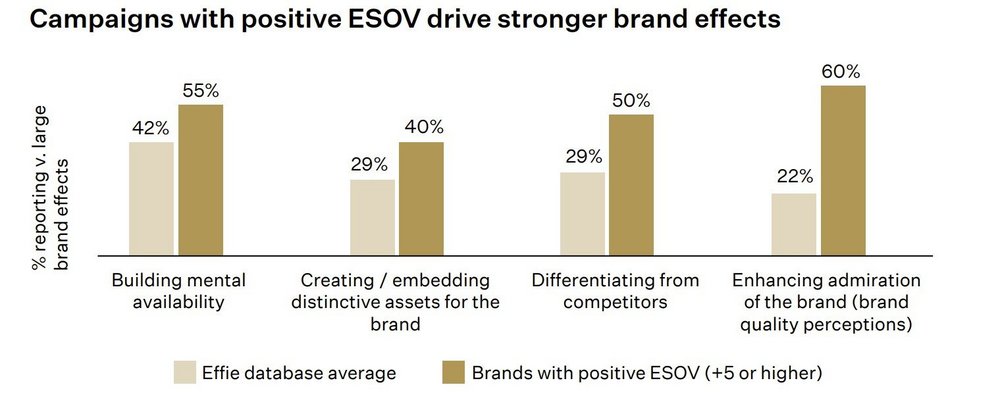

It uses the ACA’s Effectiveness Database to demonstrate the power of Extra Share of Voice (ESOV), which refers to the amount by which a brand’s share of the total category ad spend exceeds its market share.

Until now research had only looked at the impact of ESOV on market share. But Brittain and Field used ACA’s Effectiveness Database to show that ESOV is positively linked with a wider range of brand and business metrics, including mental availability (how likely a brand is to be considered for a consumption occasion) and pricing power.

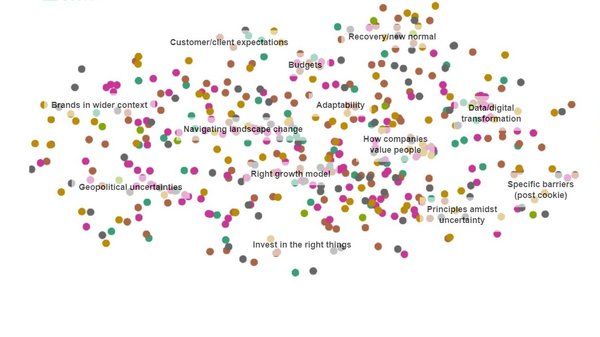

The report also states that share of search is valuable but not suited to replace SOV. It claims that share of search does not take into account category growth, or external sentiments or events not controlled by the brand (for instance, the Volkswagen emissions scandal), and it argues that not every category is searched frequently enough to produce useful results.

The report also points out that share of search can only be measured when a brand is already well-known enough for people to use it in an online search query, which means that it is ‘an outcome of other marketing activity that occurred before it’.

James Hankins, who runs strategy consultancy Vizer and was one of the earliest proponents of share of search, had this to say about the report’s claims regarding share of search:

‘I agree with the conclusion here about SOS not being a replacement for SOV, this could arguably be labelled “Ritson’s Folly” as it was his Marketing Week article that started the confusion. However, I also note that there are also some incorrect assumptions with regards the metric itself. SOS is a proxy (and consistently accurate directional proxy, too) for share of market, and it works across category whether that category has a long or short buying cycle (it’s been validated for FMCG as well as car buying, for example).

‘Sentiment based “fluctuations” are easily minimised by smoothing the data, with 12-month averages being an easy technique with which to do this. As a proxy for SOM, a metric that many companies don’t have access to, it signals winning relative to the other category players (whether the category is growing or not). Ultimately though, it’s worth remembering that SOS is a demand-led measure, so supply shocks and physical or digital availability issues won’t always be apparent. There is further research in this area occurring at the moment which will be shared in due course.

‘SOS doesn’t pretend to be a universal metric but as the paper suggests it should be a KPI when allied to other important metrics. For the clever analyst who understands its true limits and doesn’t rely on it solely, it enhances any view of a categories dynamics.’

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.