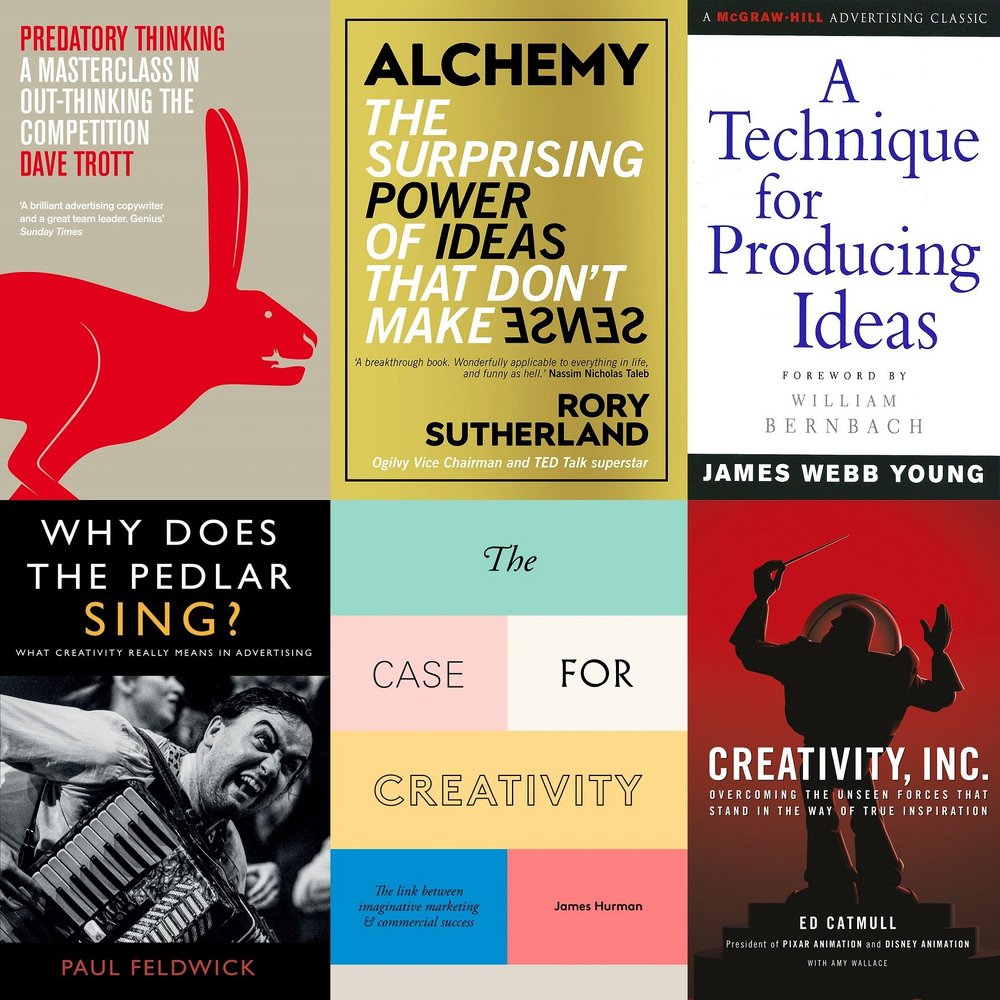

Contagious recommends: 9 books every advertising creative should read /

Books that explain and inspire creativity

Creativity is an amorphous thing and writing about it can sometimes feel like trying to nail smoke to a wall.

But there are authors who have succeeded in bringing insight and clarity to the subject.

These are the books, in no particular order, that Contagious’ editors and strategists have found the most useful for understanding the processes that lead to original thinking, as well as creativity’s role within advertising.

1. Why Does the Pedlar Sing? by Paul Feldwick /

As the old adage tells us, ‘They don’t call it show business for nothing,’ and Paul Feldwick’s book Why Does the Pedlar Sing? is an urgent reminder to his own industry that selling and entertainment go hand in hand – or at least that they did, and they probably still should.

It’s not a fashionable view, but Feldwick’s case is compelling and thorough. He argues that Adland’s relentless quest for rationality, respectability and, increasingly, awards has come at the expense of popularity and efficacy; that the industry is playing to its peer group rather than to The People.

To show us how we got here, Feldwick takes us back to the days before mass media, when guile and showmanship – the ability to gather and hold a crowd – were an established route to commercial success.

He draws a line from the patter and performance of itinerant hawkers to the scale and ambition of PT Barnum’s energetic pursuit of celebrity and spectacle. Indeed, the author sees the impresario’s instinctive ability to manufacture fame as a template for the modern business of building brands. ‘Barnum understood from the outset not just how to work the media, and how to work the crowd,’ says Feldwick, ‘he also understood how to use the media to influence the crowd and how to use the crowd to influence the media.’

Feldwick also argues that the creation of fame is the most important role of advertising, making a link from the bombast of Barnum to the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute’s well-researched model for how brands grow. The relatively dry language of mental and physical availability has won over a generation of marketers: the point Feldwick drives home is that the hard science of Sharp and Romaniuk backs up the enduring efficacy of the soft sell.

The difficulty, of course, is that the stuff that people respond to – playfulness, rhyme, jingles, characters, humour, storytelling – is not especially cool, and Feldwick has thoughts on that too… We’re huge fans of, and believers in, the commercial impact of creativity at Contagious, but Feldwick’s analysis of the cultish status that’s grown up around ‘the C-word’ offers a mind-broadening perspective that everyone in advertising would benefit from studying.

In fact, whether you work client-side, or in an agency, if you want your advertising to refresh the parts other brands cannot reach, Why Does the Pedlar Sing? should be required reading. Simples.

Key quote: ‘If there is a choice to be made between efficiency and thinking big, you cannot afford to be efficient if you want to be famous’

By Katrina Stirton Dodd, editor-at-large

2. Predatory Thinking, by Dave Trott /

Predatory Thinking is Aesop’s Fables for advertising.

There’s really not much more to it than that.

Trott tells anecdotes from his own life and career, from history and the news, and then explains how they demonstrate creativity.

And he does it in his own inimitable style.

One sentence per paragraph.

I say inimitable, but if anything it’s too imitable.

Lots of people write like this now, especially on LinkedIn, where it is sometimes called ‘broetry’.

Trott is better at it than most, though.

I suspect that he occasionally embellishes or simplifies his anecdotes to fit a narrative but that’s forgivable.

The book’s job is to inspire creative thinking and it does that job well.

If Predatory Thinking has a theme it is that creativity is not aesthetics but a ruthless mindset that changes contexts to solve problems.

It’s probably not the first book you should read to understand advertising and definitely not the only one, but you absolutely should read it.

It’s entertaining and incredibly easy to digest.

Pop it next to your loo and you’ll be done in a couple of weeks.

Depending on how regular you are.

Key Quote: ‘90% of thinking ignores the context.

Which is why most thinking doesn’t work.

What works is out-thinking the problem.

Faced with a problem you can’t solve, get up stream and change the context.

Change it to a problem you can solve.’

By James Swift, online editor

3. Alchemy: The Surprising Power of Ideas That Don't Make Sense, by Rory Sutherland /

While I’m almost certain that Spectator columnist Rory Sutherland doesn’t share my particular brand of politics, I can think of no adland figure I’d rather find myself sitting beside at a dinner party. In our polarised times, this fanboy admission must surely serve as the most ringing of endorsements for just how captivating a man Sutherland can be.

His book makes a compelling and fascinating case for irrational thinking in a world that is seemingly increasingly enraptured by logic. Put another way, it is the complete antithesis of just about anything you’re likely to find in a management consultant’s PowerPoint presentation.

The book’s central focus is on relentlessly demonstrating how nonsensical ideas have a peculiar capacity to unlock tricky briefs. One observation that Sutherland muses on in the early chapters is that human beings are inherently irrational creatures. Indeed, he points out that rationality is not necessarily an evolutionary advantage, and as a result hasn’t been selected for over millennia; the thought being that rationality merely serves to breed predictability, which in turn only results in you ending up as someone’s lunch.

As such, the lessons for brand managers, advertisers, and innovators are clear. Where others zig, you must nearly always endeavour to zag. Human beings are complex entities that are influenced by myriad elements depending on the context. We are not quite as easy to hack as Cambridge Analytica might have had you believe. Sometimes the illogical and the absurd can win the day and, my God, doesn’t that make things just a little bit more interesting? However, a public-service word of warning before you begin – this book will fundamentally change the way you look at the world. Your significant other may not thank you for the counter-intuitive lens you will subsequently begin to apply to absolutely everything in your life.

Key Quote: ‘Suffice to say that the human mind does not run on logic any more than a horse runs on petrol.’

By David Beresford, strategist

4. The Case for Creativity, by James Hurman /

The Case for Creativity should be the go-to book for anyone that needs to arm themselves with arguments about the power of creativity to drive business results. It’s small enough to fit in a coat pocket, comes in at under 200 pages and is written in such a simple, accessible style (as you might expect from a former planner) you can easily whip through it in a single sitting. Yet it manages to distil the findings of three decades of academic research exploring the role creativity plays in advertising effectiveness.

Hurman does a particularly good job of summarising the research of Les Binet and Peter Field in this area – a welcome relief to anyone who has tried to read the somewhat dry Marketing in the Era of Accountability or The Link between Creativity and Effectiveness. Hurman does more than set out proof points, however. He also comes to the defence of creative agencies, looks at the correlation between creative corporate cultures and market performance and – perhaps unsurprisingly given that the publisher of the second edition is Cannes Lions – makes the case for creative awards.

But for me the most interesting chapters are the ones where Hurman defines the characteristics of creativity and unpacks how it works to drive effectiveness. In my experience working with organisations to build creative excellence programmes, one challenge they often have is a lack of a shared definition of creativity, or a way for their marketers to evaluate work or set expectations with their agencies. This can be a useful first step in fostering creative ambition at an organisational level. Hurman’s definition states that creativity should be original, engaging, executed with craft and used ‘to solve problems and sell products. To create things of real value rather than shit.’ That seems a good place to start.

I also love the case he makes for originality. He puts forward the concept of ‘cognitive immunity’ to describe the way our brains filter out ideas we’ve seen before, just as our bodies put up defences against viruses we’ve been exposed to before. It’s a powerful image, and although it doesn’t feel quite right talking about viruses in the current climate, it’s one I’ve stolen for many presentations.

Now more than a decade old, the book may be missing some of the more recent discussions around the crisis in effectiveness and the impact of increased online spend, and the influence of Byron Sharp et al feels strangely lacking. However, the evidence is robust, the arguments have stood the test of time, and the book is so packed with great quotes (Bill Bernbach’s ‘If your advertising goes unnoticed, the rest is academic’ is one of my favourites), that there’s plenty in there for you to steal to make your own case for creativity today.

Key quote: ‘Highly creative but ineffective work is extremely rare, but very noticeable because it wins awards. What’s less noticeable, but without doubt of far greater cost to the business community, is the gargantuan amount of uncreative advertising that creates no return on its investment.’

By Georgia Malden, lead strategist

5. A Technique for Producing Ideas, by James Webb Young /

Even creative people struggle to articulate how they actually come up with ideas. David Lynch talks about how they’re like fish (‘You don't make the fish, you catch the fish’. Thanks Dave…), while Neil Gaiman glibly tells people that he gets his ideas from the Idea-of-the-Month Club. It’s an arcane, shadowy practice that is far more comfortable being post-rationalised than pinned down. Which is why we’re such fans of James Webb Young’s A Technique for Producing Ideas.

The adman and first chairman of the Advertising Council’s book codifies the creative process into a practical guide for coming up with the things that normally appear with an ‘air of magic and unaccountability’. And unlike some advertising books, which barely had enough material to fill a single tweet, A Technique for Producing Ideas nails the subject concisely in less than 50 pages. In fact, towards the end of the book, Webb sums up the whole process in a scant 80 words.

Webb’s five-step process may not be entirely revelatory, but it’s hugely confidence-building to see the inefficient, messy workings of the mind laid out as actually the most efficient and clean method for coming up with ideas. But, while it’s short and practical, we’ll leave you with the warning that Webb himself included in the text:

(Key Quote) ‘The formula is so simple to state that few who hear it really believe in it. [But], while simple to state, it actually requires the hardest kind of intellectual work to follow, so that not all who accept it use it. Thus I broadcast this formula with no real fear of glutting the market in which I make my living.’

By Alex Jenkins, editorial director

6. Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration, By Ed Catmull, with Amy Wallace /

I read Creativity Inc, written by the co-founder of Pixar and president of Walt Disney Animation Studios, Ed Catmull, shortly after it came out in 2014. I was intrigued by a New York Times piece that described it as ‘the latest bible for the show business crowd’, but I now believe it is fundamental reading for anyone who works in a creative industry.

Though not exactly a memoir, the book draws on Catmull’s life and how he helped set up Pixar to share valuable lessons on building and sustaining a creative culture. A key theme is nurturing ideas, or in Catmull’s straight-talking vernacular, getting them ‘from suck to not-suck’. Creativity Inc describes how at Pixar the Braintrust is an instrumental tool for this. This group of advisors meets throughout the film-making process to provide feedback, which the director can choose to take or leave. The brilliance of the Braintrust is that it recognises how ‘people who take on complicated creative projects become lost at some point in the process’ and establishes a process to help them find their way. For a Disney / Pixar fan like me, it was fascinating to read about the Braintrust’s impact on Pixar gems like Inside Out and Toy Story.

There’s also much to learn from Ed Catmull’s views on leadership, in particular how important it is for leaders to show humility and empower others to solve problems without asking for permission. Anyone working in advertising, where creative directors are so often deified, should also stop to ponder Catmull’s dismissive attitude towards hierarchy. ‘When it comes to creative inspiration, job titles and hierarchy are meaningless,’ he writes, arguing that people at any level should be able to provide honest feedback.

While Catmull’s anecdotes about the early days of Pixar and working with Steve Jobs make this book entertaining, his advice on feedback, failure and leadership make it illuminating.

Key quote: ‘You are not your idea, and if you identify too closely with your ideas, you will take offense when they are challenged.’

By Chloe Markowicz, editor

7. Ogilvy On Advertising, by David Ogilvy /

No one, when listing the giants of twentieth-century advertising, could omit David Ogilvy – ‘the father of advertising’. Ogilvy On Advertising (1983) was his second book, after 1963’s Confessions Of An Advertising Man. The book is a general commentary on the advertising industry, divided into twenty chapters, covering everything from the characteristics of effective advertising, to the art of winning new business, to the manifold benefits of robust research.

Strangely perhaps, for an article that aims to endorse a book, I’m going to start with the various reasons for not reading Ogilvy On Advertising, because there are many. Firstly, it is a book acutely of its time. Much of the content, from financial information to analysis of media, is firmly out of date. Many of its chapters are either weirdly niche (Chapter 10: How to advertise foreign travel) or of limited relevance to the vast majority of readers (Chapter 4: How to run an advertising agency). And it doesn’t help that many of Ogilvy’s 13 predictions in the final chapter have singularly failed to materialise.

And yet, I believe that everyone working in advertising should take the time to read this short book. In Anatomy of Humbug, Paul Feldwick observes that ‘the default position for most advertising people was, and still is, that the past is irrelevant’. Byron Sharp in How Brands Grow similarly bemoans the ‘anything goes’ attitude of modern marketers. Ogilvy On Advertising deepens the roots of our understanding of advertising practice, by providing a valuable window into the philosophy and working habits of one of the industry’s most successful proponents. We are reminded of the importance of grabbing and holding your audience’s attention, of having a clear position for your product, and of formal research processes, so long as they are not misused (‘using research as a drunkard uses a lamppost – not for illumination but for support’). The book contains a gratifyingly extensive selection of executions from some of the most iconic and influential mid-twentieth-century advertising campaigns. But perhaps most importantly, the book reminds us of the absolute commercial imperative when developing advertising campaigns – the defining mantra of David Ogilvy’s agency was ‘We sell or else’. Ogilvy quotes Claude Hopkins, saying disparagingly of many advertising practitioners: ‘instead of sales, they seek applause’.

The Spanish philosopher George Santayana observed that ‘those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’. If those working in advertising do not consider the hard-won lessons of their predecessors, and there is perhaps no better sage than David Ogilvy, then the industry will continue to leave money on the table.

Key Quote: ‘When I write an advertisement, I don’t want you to tell me that you find it “creative”. I want you to find it so interesting that you buy the product’

By James Womersley, senior strategist

8. Anatomy of Humbug: How to Think Differently About Advertising, by Paul Feldwick /

As the title would suggest, this book provides a dissection of our discipline – call it commercial creativity, advertising or simply humbug. But it bears no resemblance to the turgid, dense marketing texts you might see next to it on a planner’s shelf.

This is the book on creativity that everybody should read. It is entertaining, informative, understated, and so beautifully readable, which having read my fair share of creativity and marketing books, I must say is not a given. And yes, that’s twice I’ve made that point in two paragraphs, but I feel pretty strongly about it.

The book is written by Paul Feldwick, a planner by trade whose passion and love for our industry and what it creates bleeds through the pages. At its heart, this is a curiosity-driven exploration of advertising history, which encourages readers to reflect on how we think advertising works and why we think that way. It covers concepts from USPs to AIDA, and social connection to spin, unpicking how these ideas took hold and the implications they have today.

Split in three parts, it travels from salesmanship (the rational roots of using creativity to commercial effect) to seduction (the coup of art, emotion and manipulation) and ends with a roundup of other influential thinking (from Paul Watzlawick to PT Barnum).

Sure, it’ll teach you the history of advertising and where the established and seemingly accepted frameworks and models come from, but the beauty of this book is that by dispelling much of the lore that surrounds adland and sharing facts that illuminate the ‘art vs science’ debate, it helps you to think better. And as creativity moves into ever more unchartered spaces, it unshackles us from the hang-ups of the past.

Understanding what came before, liberates us all to develop our own perspective – crucially, in an informed way. It gives its readers the good sense to avoid buying into the latest craze, bowing down to the most revered title or giving into the imposter syndrome that you’re less smart than everyone else.

Must. Read.

By Becca Peel, senior strategist

9. On Creativity, by Isaac Asimov /

Isaac Asimov’s 1,500-word essay on encouraging new ideas is not a book and in all likelihood was never even meant to be published. But it contains so much insight into the nature of creativity and such clear-eyed advice on how to coax it out of people that we were willing to corrupt our own format to include it in this list.

Asimov, a science fiction author and biochemistry professor, wrote On Creativity in 1959 after he was asked to join a group contracted by the US government to provide ‘out of the box’ ideas for ballistic missile defence systems.

It was a singular project (and one that Asimov quickly deserted) but the essay that Asimov wrote at the outset to help guide his colleagues is universal.

After a short meditation on creative breakthroughs and the kind of people most likely to have them – explained via Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace’s simultaneous discovery of natural selection – Asimov gets to the nuts and bolts of generating new ideas.

In a nutshell, Asimov’s advice is for creatives to think in isolation and then meet as a group to share progress, to spark new combinations of thoughts. None of that is shocking or unorthodox, but there is something compelling about the way Asimov never seems in thrall to creativity. For him, it’s all about the supply of information and the right working conditions. It is an entirely practicable doctrine, perhaps even prosaic, and that is why it is inspiring – because it makes original thinking seem attainable.

I haven’t done the legwork to be able to say with confidence that Asimov’s essay is the best exploration of creativity ever written, but I doubt there exists anything better that can fit on two sides of A4 paper.

Key Quote: ‘The person who is most likely to get new ideas is a person of good background in the field of interest and one who is unconventional in his habits. (To be a crackpot is not, however, enough in itself.)’

By James Swift, online editor

The Contagious Commandments: Ten Steps to Brand Bravery, by Paul Kemp-Robertson and Chris Barth /

Come on, we were always going to mention The Contagious Commandments. In fact, we think we showed remarkable restraint by keeping it out of the main list and not calling this article ‘8 books about creativity that are almost as good as ours’. And a decade of Contagious knowledge and case studies condensed into a single volume has got to worth a click, right?

You can also get a quick tour of the 10 Contagious Commandments, here.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.