“Fast fast, fail often,” is good advice for certain contexts and terribly bad advice for others’ /

Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson explains what we get wrong about failure and how embracing errors can help companies become more creative

Adam Richmond

/

Failure is having quite a cultural moment, cemented by none other than Taylor Swift in an awards speech last year: ‘I really want everyone to know that the hundreds or thousands of dumb ideas I’ve had are what led me to my good ideas. You have to give yourself permission to fail.’

The current queen of pop is not the first to celebrate the importance of reframing setbacks as opportunities for personal growth. In Silicon Valley, for example, failure has been a long-time badge of honour – the San Franciscan tech try-hards notably got their very own FailCon in 2009. But Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson bristles at the ‘fail fast, fail often’ mantra of tech startups. She maintains it’s an approach that leads to sloppy thinking when applied to the realities of everyday of work, as it doesn’t distinguish good failure from bad.

Edmondson is exceedingly well equipped to put the tech bros in their place on this matter; after all she has been researching failure for two decades. Her journey began with an exploration into whether better teamwork in hospitals led to fewer medication errors. The initial findings flew in the face of her hypothesis and showed that better teams actually had higher error rates. Sitting with this distinct failure ultimately led Edmondson to a game-changing revelation: good teams don’t make more mistakes, they report more. This insight formed the bedrock for her pioneering work into ‘psychological safety’ – the idea that work environments that encourage people to speak up about mistakes, share differences of opinion, and ask for help if in over their head will eliminate preventable errors and cultivate an atmosphere of risk-taking and innovation.

Edmondson’s latest book, Right Kind of Wrong: The Science of Failing Well, provides a framework for how to pursue smart risks while preventing avoidable harm – backed up by academic research and compelling real world gaffes, blunders and oversights. Contagious sits down with the academic to explore the connection between failure and creativity, and understand how managers can create a work environment that supports the right kind of failure.

Why is it so hard learning how to admit failure?

Amy Edmondson: There’s two big forces at work. One has to do with human nature, and the other has to do with our socialisation and the social context in which we find ourselves – meaning, our life-long socialisation and the social context of our organisations or families. Both factors lead us to have a very strong desire to want to look good in the eyes of others, evolutionarily speaking, leaving us with this worry and anxiety about rejection. And so if you see me as the fallible human being that I am, maybe you will reject me from the tribe and I will die of exposure or starvation, or both.

So there’s that kind of desire to belong, desire to be seen, to be approved. And meanwhile, those exact same forces characterise most of our organisational lives; we want others to think we are capable, likeable, competent. So we are prone to hide our imperfections, to not speak up when we need help when we’re in over our head, to not want to admit mistakes, or even larger failures.

It’s hard to not equate fallibility with weakness, right?

It’s a fundamental error that most of us make, which is we think people will like us if we’re perfect and shiny – you’re going want me in your friend group if I’m infallible – when in reality, real bonds, real relationships are built through our fallibility, through connection when I realise, ‘oh, you struggle with that too’. I like you more, I feel more comfortable with you. It’s this kind of error that we make when we think if we put on a show you’ll like me more when, in fact, you’d like me more when I’m real.

Amy Edmondson

You take issue with the ‘fail fast, fail often’ mantra of Silicon Valley. Why?

It is terribly good advice for certain contexts and terribly bad advice for others. So in which context does this idea ‘fail fast, fail often’ work? Well, number one, novel contexts or contexts where the only way to make progress is through trial and failure – through coming up with something, giving it a whirl and then seeing what happens because there’s no playbook yet. [But] it’s at risk of sounding like anything goes, just throw the darts at the wall.

I think that it also misses a bit of clarity in that failing fast ought to be with well-reasoned hypotheses; you’re trying something but your experience gives you good reason to believe it might work. You’re not setting out to fail, you’re setting out to make progress. You are well aware that because of the novelty of the terrain, that progress may end in failure, but that’s the way forward, so all of that it makes good sense. Whereas in familiar territory, where there is a recipe or there is a playbook, our best advice is ‘please use it’ – be on the lookout for ways that you can improve that recipe, improve that playbook, but put it to good use and put it to use with vigilance to get the results that you want.

If you say ‘fail fast, fail often’ and you’re an entrepreneur, coming up with some new app, sure, that’s great. If you said ‘fail fast, fail often’ to the plant manager of an automotive assembly line, they would look at you like, ‘Are you kidding me?’ That’s just not helpful in any way, shape or form.

There’s that management idea that ‘failure is not an option’.

That wonderful quote is attributed to Gene Kranz at Nasa during the time of the Apollo 13 failure crisis, where the craft lost an oxygen tank – a serious failure in space. When Kranz says ‘failure is not an option’, what he is saying is, ‘I believe, with our engineering talent, our ingenuity, our effort, we can solve this because failure is unthinkable.’ He’s not saying ‘Don’t speak to me about it.’ But it’s often misinterpreted. If senior leaders are saying failure is not an option, what are the junior people doing? Well, they’re just hiding the failures, of course, versus with [Kranz’s] kind of inspirational statement of confidence in the team, that they would be able to solve this one, challenging though it was.

Can you speak to the disruptive and innovative power of error? You use the example of the happy accident that led to the creation of oyster sauce...

We all make mistakes, and most of our mistakes have bad outcomes that range between a moment of inconvenience to something catastrophic. But occasionally, a mistake is made that leads to a wonderful eureka moment of discovery, a happy accident. And in 1888, Lee Kum Kee was a young chef, cooking oysters in a little restaurant in Guangdong Province of China, when he accidentally made a mistake, left the pot on the stove for too long, came back and discovered not lovely cooked oysters but a sticky brown mess.

I think most of us would have gone to the sink with that pot and washed it – get that glue off and start over with your dish. But not Mr Lee. He tasted the goo and discovered that it was delicious. That was the birth of oyster sauce.

An open mind and self-awareness transcends all of these different kinds of failures. And whether it’s a basic mistake, like oyster sauce, or a more complex failure, having an open mind, being aware, being curious, being alert, is crucial to best practice.

Amy Edmondson

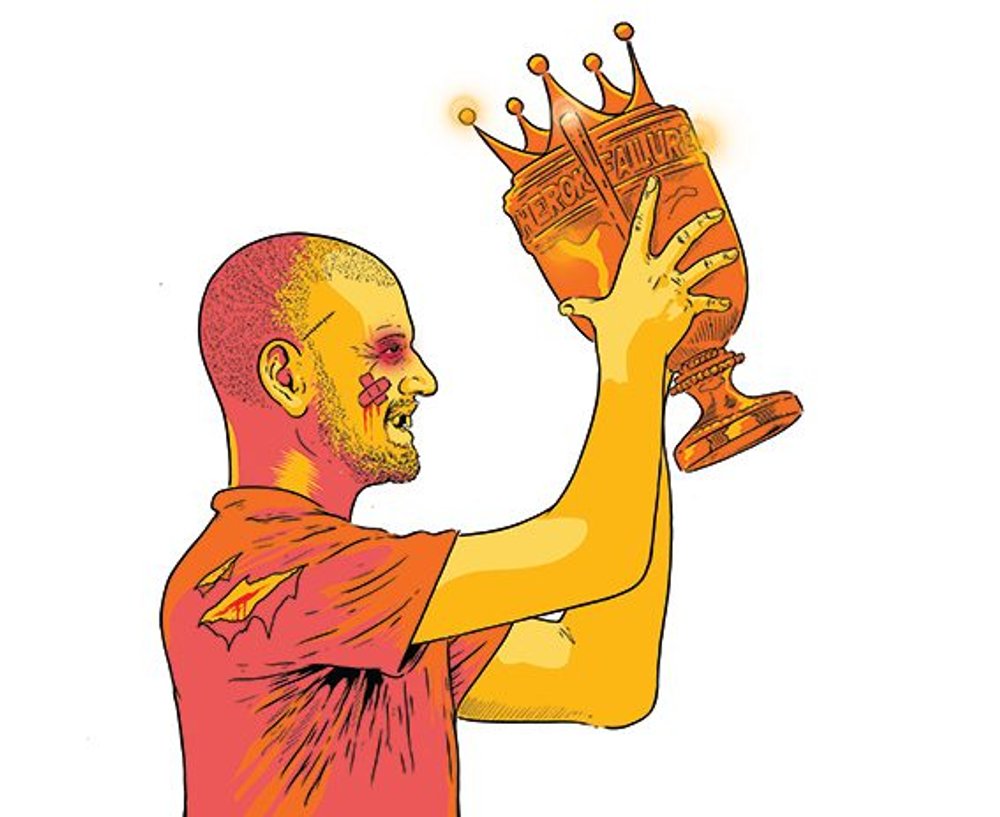

How can creatives in particular learn from failure? The book uses the example of Tor Myrhen (now vice president of marketing communications at Apple) coming up with the Heroic Failure Award when he was at Grey...

It’s not often made crystal clear that if your company is going to have a Heroic Failure Award, it will not be an award for someone who just showed up at work drunk and screwed up the automobile assembly line that day. That would be a failure to be sure, but that would not be the kind of thing we would reward. What we reward is someone who goes out on a limb and takes a smart risk that nonetheless yields failure. And that is a context and an activity that is far more likely to happen in creative industries like advertising and new product development than in more routine, well-understood domains.

In the case of the Heroic Failure Award at Grey Advertising, the leader was worried that people were playing it safe. So they were trying to encourage more wild ideas. Now, not all wild ideas will be appreciated by your client – that’s the failure part. If you think a team member has come up with something really creative and edgy, but the client hates it, that’s an opportunity for a Heroic Failure Award. What you’re trying to say is, ‘I don’t care whether they didn’t like it. I still value you and value the behaviour of going out on a limb with something new and edgy.’ Because otherwise what are people going to do? They’re just going to retreat to their safe territory again.

Amy Edmondson

How do team leaders create a workplace that supports the right kind of failure?

There are a few things that managers can and really must do. One is call attention to uncertainty. Uncertainty can be very, very low, as in an automotive assembly line, or very, very high, as in an ad campaign where you’re trying to win a client – who knows what they’re going to like or what’s going to work. By calling attention to uncertainty, you are helping people understand how much room they have to experiment, which is either very, very small or very high. So you’re intellectually clarifying the nature of the game we’re playing here.

And then modelling your own curiosity, showing up as a person who wonders, who’s creative, who’s curious – you’re asking people questions, what are you seeing out there? What ideas do you have? What are we missing? That’s the kind of leadership that promotes healthy failure and promotes speaking up about deviations or imperfections in known contexts to help prevent basic failures.

And finally, possibly most importantly, you are responding productively. Your response when someone brings you a failure, you’re saying ‘I am so glad you tried it, because I love it’ or ‘It was wonderful to see something out-there for a change’. You’re blessing it, you’re rewarding it, rather than inadvertently or explicitly punishing it.

How can the systems in which we work best promote creativity or innovation? You’ve cited 3M’s system and how it led to the invention of the Post-it note.

3M as a company is famously set up to innovate. It isn’t one thing, it’s multiple things. It’s a system conducive to innovation, a system that includes everything. They were pioneers in giving scientists and employees the opportunity to spend 15% of their time each week doing whatever they want, to see what happens – it doesn’t have to be productive and efficient. That focus on efficiency, it’s hard to overstate the degree to which that was the zeitgeist in almost every company for the longest time.

To say ‘take 15% of your time and do something unproductive’ wasn’t normal. But it’s now widely copied, especially in the tech industry. Failures are still undesired, even for scientists and inventors. They would rather their first hypothesis yielded a billion dollar product, but they understand that’s just not how it really works.

Amy Edmondson

You talk about the importance of apology with regard to failure. A lot of brands could learn how to apologise better...

If you’ve had a failure, or you’ve done something wrong, you’ve ruptured the relationship – and that is true between two people, but that’s also the relationship between a brand and its customers. When you experience a failure, small or large, you’ve got to quickly try to do what you can to repair that relationship and an apology plays a role in that. And the essential elements of an apology that works is that it acknowledges what happened, what you did wrong, and takes accountability. It doesn’t say I was in a hurry, or I was under pressure, or it wasn’t my fault. Then you’re willing to acknowledge the thing that went wrong and that you played a role in it. And finally, an offer of making amends, whether it’s to do better next time or to compensate anyone harmed. Those are the elements of an effective apology and when any one of those is missing it doesn’t do its repair work quite as well.

What’s wrong about the idea of holding people accountable for their mistakes?

When you come down on the side of accountability, which is often code for punishment, your primary impact is one of making it less likely that you’ll hear about mistakes. I mean, you can’t hide big bad failures, but there are plenty of things that go wrong that will just not come to light, so you are at risk of being kept in the dark more than you are likely to genuinely improve motivation. So that’s one factor. You’ve created this risk when you say we’re going to punish people for these things going wrong, word will spread more slowly.

Number two, and more maybe more fundamental, is that fear is not a very good motivator in the human psyche. We are motivated to avoid certain things by fear, but we’re not motivated by fear to stretch and grow, and do our very best. We’re motivated to stay looking good, looking valuable, but not to actually do the things we need to do to be good and be valuable.

What motivates us more is purpose – the opportunity to accomplish something that we can be proud of, the opportunity to work with others on something exciting that we believe matters. A deeper understanding of human motivation realises that the best way to get excellence is not punish people when things go wrong, [rather] make sure you help people truly believe that what they’re doing matters and make them want to do well at it.

How to fail well /

‘Failure is a fact of life. Failing is not a matter of if but when and how’

Reflect out loud / When things go pear-shaped, really consider the question: what didn’t go well? Edmondson writes in The Right Kind of Wrong, ‘Failures are opportunities for improvement,’ – so normalise failure, say what isn’t going well so that your team can all help make it better. Have the courage to be honest with yourself. This also models a healthy attitude to failure that will encourage all team members to speak up.

Choose your words wisely / Reframe how you refer to things. When it comes to reflecting on a failure, instead of using words like ‘investigation’, opt for something less legal, such as ‘study’. This helps shift from a blaming mindset to one more open to learning.

See the bigger picture / Take a step back. Zoom out. Consider how an immediate decision affects others and plays out in the long term. The short-term response may resolve a problem in the here and now, but will a quick-fix stop it from happening again, or cause other issues down the line?

Celebrate pivots / Too often, failure is seen as an ‘ending’. In the case of the Post-it note, 3M’s Spencer Silver was trying to create a super-strong adhesive and ended up with one that was weak and pressure-sensitive. Talking to colleagues about his struggles led to connecting with co-worker Art Fry who kept losing the hymn notes from his choir book... and the rest is history. Reframe failure as the start of something new and exciting.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.