Funny times: why advertising swings between cynicism and sincerity /

Advertising's shift from irony-laden cynicism to full-throated sincerity plays to Felix Richter's strengths as a creative, but the Droga5 co-chief creative officer isn't sure it's good news for society

Contagious Contributor

/

Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash

When I started my first job in advertising in the beginning of 2010, Old Spice’s ‘The Man Your Man Could Smell Like’ had just launched during Super Bowl weekend. It was the pinnacle of a growing trend of what could be described as postmodern advertising, where the commercial uses self-reference, irony, and absurdity to acknowledge what it is: an ad, an interruption to the viewer’s entertainment.

It was a great strategy to appeal to an audience tired of ads and a way for brands to come across as clever, charming and, for once, honest.

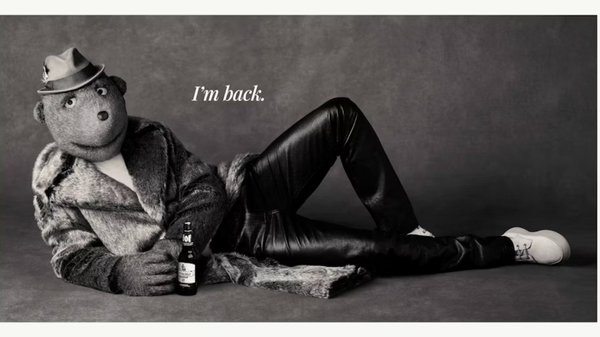

Skittles, Newcastle Brown Ale, Volvo, Virgin Atlantic – they all got the postmodern treatment. It was great and the type of work every young creative wanted in their book. Mostly, the creative approach was simple: quite literally say the brief, then have fun with it or even make fun of the brief in the ad.

I was of two minds about this kind of advertising. On one hand, I admired its cleverness and unfiltered, out-there creativity. On the other, I knew I wouldn’t be good at making these ads myself. Every creative is malleable to some extent, but there’s also a center of gravity, a core voice or type of work that comes more naturally to you than others. Funny scripts were not that for me. At one point, I took a set of ‘funny’ scripts to my CD, and when I was done presenting, he replied, ‘You just said a bunch of words and then started laughing—is that what humour in Germany is like?’

Felix Richter, Droga5

So, I worked on brands that still believed they needed a more serious tone. But with postmodern ads universally celebrated, it felt like making serious, inspirational work was increasingly hard. In a climate of constant irony, any attempt to inspire or move people—or to be earnest—feels hopelessly contrived from the start or, at the very least, naïve.

Of course, the industry was then, as it is now, just echoing the zeitgeist. For at least a decade, movies, TV and literature had offered a constant stream of cynical, self-referential and ironic content (Fight Club, South Park, Family Guy). Culturally, it was the age of the hipster, who, instead of standing for any clear set of values, parodied the previous subcultures and countercultures like punks and beatniks or, on the other end of the spectrum, ultra-masculine Midwestern archetypes. Skinny Jeans, link chains, plaid shirts, long beards and John Deere hats—all were worn to express something other than what they once stood for.

Photo by Abby Savage on Unsplash

A good analysis of the phenomenon could be found in an earlier David Foster Wallace’s essay, E Pluribus Unum: Television and US Culture. In it, he describes post-TV culture as a parroting contest in which those who are trying to be genuine inevitably lose, pointing out that irony relies on the ridicule of sincerity and that, in a climate of constant irony, anything earnest will be considered bland or cheesy. I remember feeling convinced that he was right and that it would be impossible to break out of this cycle of self-reference and implicit ridicule and that advertising, along with everything else in creative culture, would forever spin into more ironic, absurd, meta ways of being.

But I was wrong.

It’s hard to say exactly how it happened, but at some point, our creative culture performed a solid 180-degree turn.

It could be that the mechanics of social media and a combination of huge societal problems made the postmodern attitude inappropriate. It could be the compounding effects of the financial crisis, increasing inequality, the threat of environmental collapse, the erosion of fact-based truths as the basis for universally shared narratives and, lately, a global pandemic, made clever, self-deprecating humor seem tone deaf and trivial.

Or perhaps the postmodern attitude overplayed its hand and sort of ruined itself.

While irony and sarcasm were once considered the most intelligent forms of humor, in the online world, winding people up and not meaning what you say has become the game of trolls—4chan users and the like.

Whatever the reason, the creative class’ appetite for the detached smirk has vanished over the past five years. Instead, sincere efforts to drive positive change were among the most celebrated things in art and culture. The highlights for our industry include Nike’s 2019 #Equality campaign and REI’s #OptOutside, as well as a fair number of cause-related Droga5 projects. A quick look at the D&AD Yellow Pencil winners of 2020 reveals how pervasive that trend really is: only about a quarter of Yellow Pencil winners didn’t have an overt connection to a good cause or societal benefit. The cultural climate has transformed from one of cool irony to intense moralism. Now, ads that offer a point of view and stand up for their brand’s beliefs, even if it means potentially alienating a portion of their customers, are often declared the winners.

There’s a lot to like about this development. Personal tone of voice and preferences aside, it seems like a good idea to want to try and do good things, particularly in advertising, with its peculiar position in the capitalist machine. It’s also good to be able to speak sincerely without fear of ridicule and to interrogate things for their moral nutritional value before buying into them. To complain about award shows that reward the ‘moral intent of a communication over its ‘excellence in craft’ would seem petty in light of the real progress many of these celebrated projects might trigger.

Perhaps, what is worrisome is what this state of affairs in advertising suggests about society at large. The sociologist Niklas Luhmann once pointed out that ‘moralizing is the fever-like immune response of society to problems it otherwise cannot solve...and fever can be dangerous,’ which rings true, considering the tone of the recent election and the continued, increasing polarisation in the US.

So, what next? Will the moralist attitude undo itself as was the case with the postmodernist attitude before it? There is a growing stream of voices pointing out that the efforts from brands to align themselves with a noble cause feel increasingly disingenuous. It’s true that the complex realities of a globalised world and the role international brands play within it often can’t be reconciled with the messaging of morality and equality that their ads wish to portray. As a result, we might just see an abandonment of cause-led marketing and a return to the self-deprecating tone of the past.

A more cheerful outlook is that a series of recent, positive developments—the end of the pandemic in sight, a new political administration in the US, a long overdue spotlight on systemic inequality—has instilled a new sense of hope in the creative class that makes a hint of subversion feel appropriate again.

A third interpretation would be that we are simply so fatigued by the endless stream of bad news that we want to escape back into humor.

This year’s Super Bowl, which featured far more lighthearted spots than serious, cause-related ones, could be read as confirming any or all three of these ideas: brands afraid of being called out for being hypocritical are retreating from cause-led marketing and fleeing into a vanilla promotion of whatever they’re selling, a genuine return to humor as a sign of growing optimism or simple escapism.

While the tectonic plates of creative trends will keep shifting back and forth beneath our feet, one thing remains unchanged: the audience is not wooed easily. If anything, the battle for attention and trust keeps intensifying. Which means that only one thing seems certain: wherever creative advertising moves next, it will have to be very, very engaging or else it won’t stand a chance.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.