2 decades of challenger brands: what’s changed? /

Twenty years after his book Eating The Big Fish helped popularise the concept of challenger brands, Adam Morgan, partner at global strategic brand consultancy Eatbigfish, has collaborated with Malcolm Devoy, chief strategy officer at PHD EMEA, to investigate the strategies today’s challengers are using to disrupt their markets

The idea of the challenger brand has become such an integral and important part of the marketing lexicon that it is now hard to imagine our industry without it. Far from being a buzzword that came and went, challenger brands have increased rather than decreased the influence they exert on the way we think and behave as marketers and communicators. This is in large part because a fresh wave of challengers is coming through, overthrowing the codes of the categories around them. With this new wave has come a sense of a shift in power: a 2017 BCG report highlighted the $20bn move from big brands to challengers in the US in packaged goods over the previous five years, and a similar scale of change in Europe.

So it comes as no surprise that last year Adweek called challenger brands a ‘global megatrend’, what is more surprising is the residual superficiality of understanding and analysis around what it means to be a challenger today. If you had listened to most of the soundbites from the past 12 months about challengers, you could be forgiven for thinking that they are exclusively small, hip, digital communicators with influencer-led media strategies and direct-to-consumer business models. Yet we – Eatbigfish and PHD – have both specialised in working with challengers from all over the world for more than 20 years, and this simplistic, one-size-fits-all model of challengers is not what we see: the universe of challengers is more richly diverse than this, and the types of companies more varied and adaptive.

Adam Morgan and Malcolm Devoy

So we set out to interview 15 of the most interesting brands from this recent wave of challengers, from Sweden and the Netherlands, to Uganda and Australia. Our aim was to take stock of how these fresh challengers are changing the conversation in their favour by examining their strategy and media behaviours, and put the findings together with our broader challenger experience to offer a more useful, applicable dimensionalisation and model. We wanted our learning to be relevant both to the company needing to be more of a challenger themselves and to the incumbent looking apprehensively over their shoulder. The findings are summarised in our new book Overthrow II, 10 Strategies from the New Wave of Challengers.

We all know that one can no longer characterise a challenger brand as being simply about ‘little player vs big player’. Being a challenger brand today is more often about challenging something – the current criteria for choice, the prevalent category codes or dominant cultural norms – than someone. What we found in our interviews are a range of narratives expressing these different types of challengers, falling broadly into four different families:

Consumer mandate for a new choice /

These are challengers that claim to be fighting on behalf of a consumer against a dominant incumbent that is benefiting at their expense. Think of sports media upstart Copa90 fighting to give football back to the fans – despite not having the rights to show the games – through fan-focused YouTube programming. Or look at clothing challenger Universal Standard, pushing for an inclusive approach to fashion, and working to make the category of plus-size clothing obsolete by offering its full range in sizes 0-30. It is now partnering with bigger brands, such as J Crew, to help create their own inclusive ranges.

Progressive challengers /

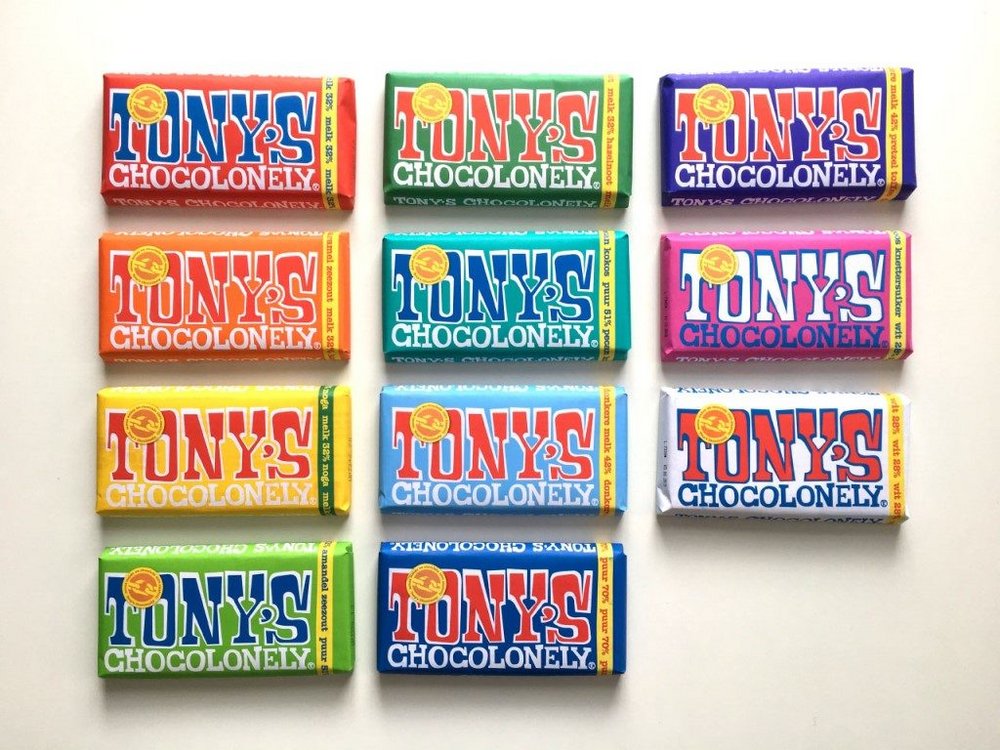

This is a group of challengers that are looking to progress the product experience or ethics of their category. Tony’s Chocolonely, for instance, is a Dutch chocolate brand focused on eradicating the often shocking labour practices in the chocolate supply chain, and campaigning to bring about 100% slave-free chocolate. Now the brand leader in the Netherlands, it is gearing up its challenge in eight further countries.

Going against the flow /

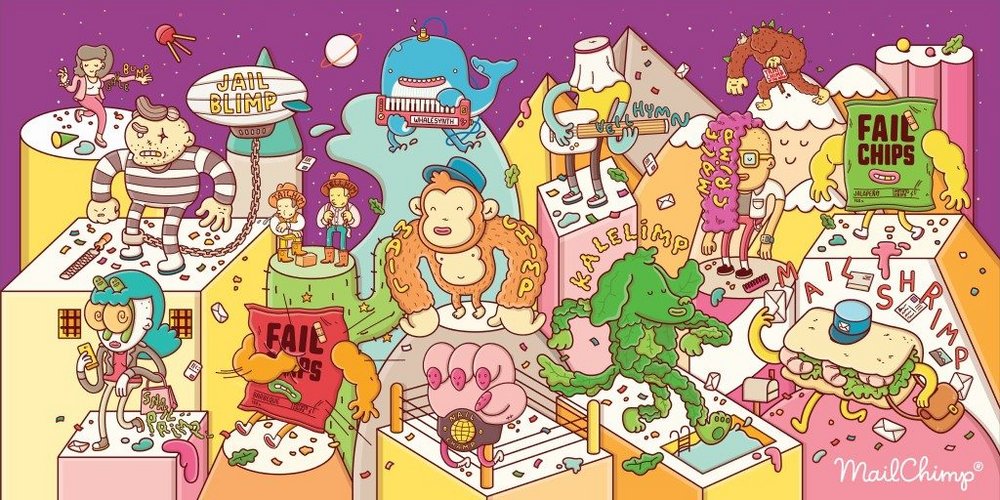

Then there are the challengers reversing what they perceive as the shortsightedness or industrialisation of the category. The furniture company Vitsoe, for instance, is championing sufficiency over consumption, and dramatises that stand by never putting its products on sale. Email marketing service Mailchimp has brought character and personality – even a little weirdness – into the previously bland world of B2B marketing platforms. Who doesn’t love getting a virtual high five from Mailchimp’s ape mascot after pressing the big red button that sends your email to subscribers?

Spirited rebels

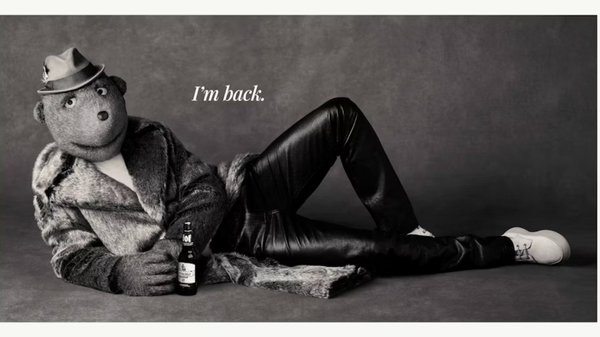

The final family of challengers is a group for whom attitude is key. Think of Under Armour poking the Nike ‘bear’ in its early years by getting its product on to NFL players when Nike was the official league sponsor, or BrewDog gleefully ripping into the sterile codes of mainstream beer.

Timely tailwinds

Those packaged goods challengers that the BCG study identified? They are, of course, part of a much broader swathe of challengers coming through in categories from media (Copa90) to finance (Monzo, Revolut), email marketing (Mailchimp) to phones (Xiaomi). Fuelling this new generation of challenger growth is a combination of lower barriers to entry (the ability to outsource everything, from manufacturing to real estate); a flood of investment and the accompanying entry of new investment companies such as The Craftory specialising in challengers; go-to-market channels opening up in the challengers’ favour (from Amazon to directto-consumer); and a flow of talent out of large companies into the new insurgents. These collective tailwinds and structural supports, says Ernie Schmitt, the co-founder of The Craftory, are here to stay. He believes this is a time of ‘seismic change’.

Adam Morgan and Malcolm Devoy

A model mindset /

While it might have begun as a strategic approach for the number two that needed to ‘try harder’, the challenger approach has become a mindset that even the largest companies find themselves required to adopt. This may be opportunistic and rooted in a chance to win share. AB InBev in Uganda, for example, saw the need to develop a beer at a price point that was much more affordable for the local market. Delivering against that price point required it to challenge itself to make a good quality beer out of an unfamiliar product (a local cereal grain called sorghum) and rethink its supply chain at the same time. The new brand, Eagle Lager, now has 50% of the Ugandan market.

At the same time there is the growing sense, for the more enlightened market leader, that taking a challenger mindset will increasingly be a defensive necessity. The then-CTO of Qantas, Rob James, announced earlier this year that he was leading a project to explore the impact that a ‘well-funded Netflix-style startup’ would have on Qantas and the Australian airline business. Shocked by the impact that challengers as different as Uber and Tesla had on the automotive business within just a five-year span, his view was that to remain resilient and relevant, Qantas needed to challenge itself before a real challenger did. (It isn’t clear how seriously Qantas is going to take James’s cri de coeur – he resigned a few months later to take up a new role at Vodafone.) More recently, P&G’s chief brand officer, Marc Pritchard, introduced an internal philosophy of ‘constructive disruption’, noting that the best way for a large company to deal with disruption was to lead with it itself.

This isn’t to argue that the future always belongs to the small. As US and Chinese tech giants unveil their own next generation of growth plans – whether expanding into new categories, such as Google’s move into gaming, or new geographies (as Alibaba’s European expansion) – there’s a counter-case to made that the alpha challengers of the next 10 years will simply be the digital powerhouses pushing into new markets.

But perhaps that simply reinforces the point. Maybe the best way to protect yourself from Amazon and Alibaba is to adopt much more of a challenger mindset. In which case the only question you have to ask yourself is: which of these different kinds of challenger do I need to be?

Looking for more Contagious content? Download for free the Most Contagious 2019 report, which includes our top 25 campaigns of the year, advice for the next decade and 4 things to put on your to-do list in 2020, here.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.