Share of search: the new most important brand metric? /

Les Binet talks to Contagious about his research into share of search as a potential predictor of share of market.

James Swift

/

(Photo by Morning Brew on Unsplash)

The internet has made it almost impossible to accurately measure brands’ share of voice, and the world seems perfectly content with that trade-off, so marketers have been forced to look for a replacement metric fit for the digital age. Share of search, it seems, might do the job.

Share of voice tells advertisers what percentage of all advertising within a particular category is theirs. It’s useful because brands that set their share of voice above their share of market tend to grow (and those that set it below tend to shrink), and marketers have used that knowledge for decades to determine their budgets.

But share of voice only works if you can reliably audit how much advertising exists in a particular category. And as more advertising shifted into dimly lit corners of the internet that task became all but impossible, to the point where most people no longer trust the data.

Les Binet, Adam&eveDDB

Les Binet, the group head of effectiveness at Adam&eveDDB, says it was about nine years ago that a colleague approached him and said, ‘we need a share of voice for the digital era’.

He started by looking at social media metrics to determine whether share of buzz – how much people are talking about a brand – could predict a brand’s share of market or its growth.

The answer is – it can’t. ‘There’s very little correlation between how much people talk about brands on social media and how those brands do in the real world,’ says Binet.

‘The brands that people talk about most on social media are the ones they’re least likely to buy. For example, in the car market the brands that people talk about most are expensive luxury brands: Porsche, Ferrari, Lotus. People don’t talk about Ford very much on social media, and certainly not Kia or Hyundai, but those are the brands they buy.’

Looking at user sentiment is no help, either. It turns out the brands that people are most likely to disparage are the ones they’re most likely to purchase. While social media is useful for some things, there’s too much bragging and wishful thinking going on for it to make a reliable replacement for share of voice.

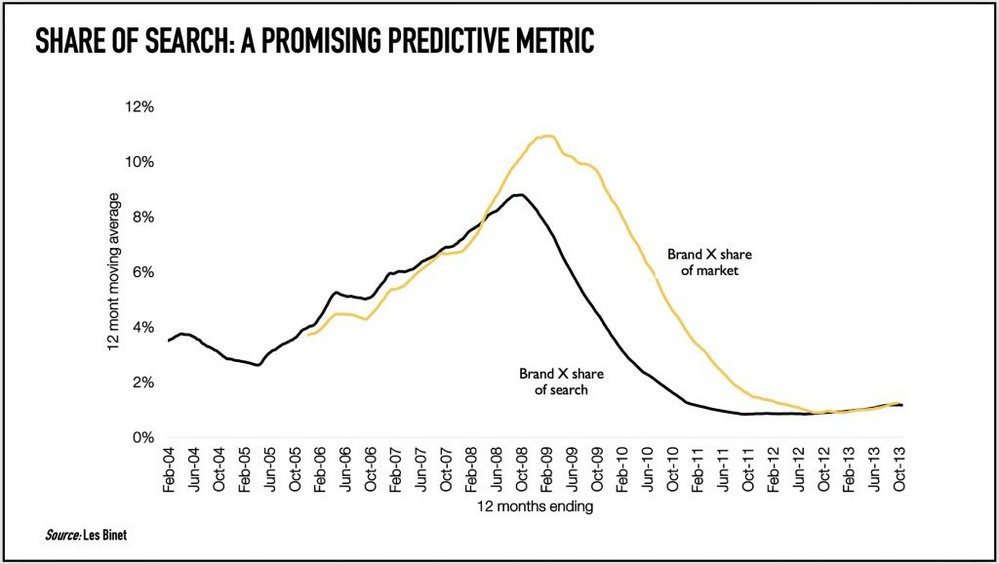

Instead Binet started looking at Google search, and after analysing three categories for which he had an abundance of data, found that share of search appeared to be correlated with share of market.

Advertisers’ have used search as an indicator of someone’s intention to buy something in the short term for almost as long as the internet has been around. It’s why you’ll get served ads programmatically for something almost as soon as you search for it. But Binet discovered long-term patterns and a two-way relationship.

A brand’s market share affects its share of search because people are more likely to want information on something they already have (if you own an Apple laptop, you’re more likely to ask questions about it). And when a brand has a high share of search relative to its size, that tends to indicate that it’s about to grow.

There’s no doubt, too, that advertising has an effect on a brand’s share of search, and others (including Google itself) have already published articles on the link between search and salience (how likely people are to think about a particular brand when making a purchase in that category). Millward Brown, for instance, cited in a 2016 white paper a US alcohol brand whose brand salience score explained ‘81% of the variation in its baseline search volumes over time’.

Binet however is tentative on the tantalising prospect that share of search can give marketers an almost immediate insight into how a brand-building ad will perform over the long term.

‘Kind of,’ he says, when asked if share of search could show brands the value of emotional advertising in days instead of years. ‘You can to some extent use it to get a prediction of the long-term effects in the short term,’ he says, ‘but it may not work in every category. It tends to work best in categories with considered purchases.’

What most excites Binet about his research, though, is that when he looked at the effects of advertising on share of search he saw – consistently across all categories – that around 40% of the impact was felt in the short term (the first month) and around 60% of the uplift was delivered over the long term (the following two years).

‘That 60/40 ratio is one I’ve seen before,’ he jokes, alluding to his earlier work with Peter Field, The Long and the Short of It, which established a 60/40 rule for brands looking to divvy up their marketing spend between long term brand building ads and short term activations. ‘So the share of search analysis provides a further piece of independent, empirical evidence for the hypothesis we have about how advertising works.

Want to create better, braver work? Join us at Most Contagious USA on 27 Jan where we’ll distil a year’s worth of advertising campaigns, insights and trends into a day of inspirational talks. Click here for the line-up and tickets

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.