Most Contagious Report

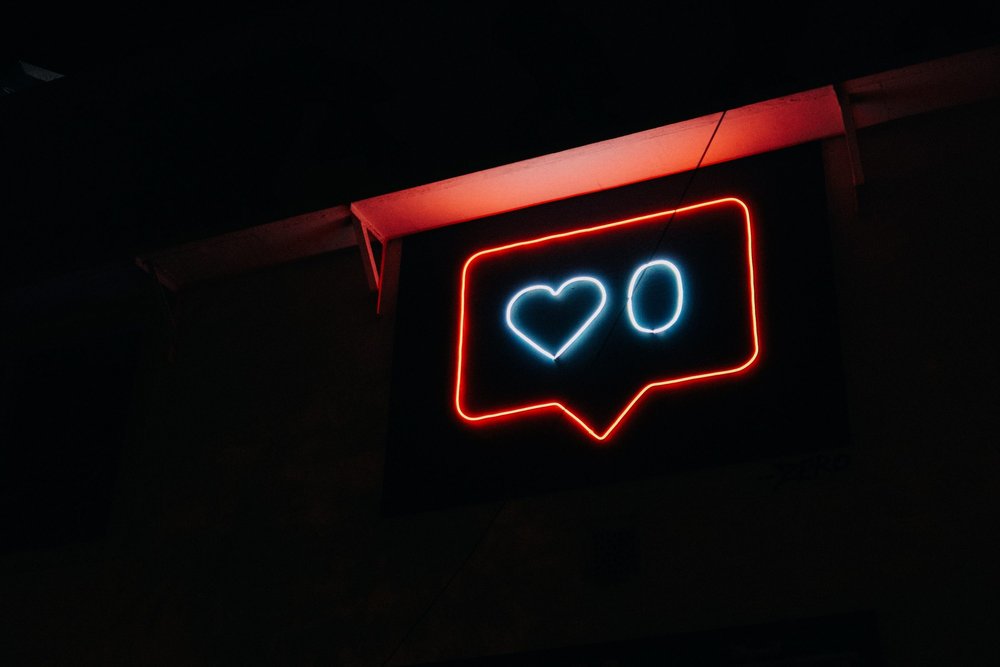

Is this the end of ‘social’ media? /

Contagious' online editor, James Swift, takes stock of what has happened to everyone’s favourite waste of time in 2023.

Photo by Prateek Katyal on Unsplash

The state of Western social media was one of the most-discussed topics in tech in 2023, and writer Cory Doctorow set the tone early in January with his blog post about ‘enshittification’.

Enshittification, he wrote, is how platforms die. ‘First, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves.’

Facebook, X (formerly Twitter) and TikTok have all succumbed to enshittification to one degree or another, argued Doctorow, and now rely on network effects to keep users coming back to a diminished experience.

Doctorow is one of the more militant critics of big tech, but his post evidently captured how a lot of people had come to feel about social media — that it was clogged with ads and influencer posts and devoid of any real social interaction. And that was before X really began to decline under Elon Musk. By the end of the summer, the New York Times, the Financial Times, and Bloomberg had all published articles about whether social media had peaked.

A new subs standard /

To some extent, Doctorow is right. Companies that operate two-sided markets where users cannot leave without incurring some social or financial cost will eventually exploit that dynamic for their own gain. That’s just capitalism. But rapaciousness only gets you part of the way to explaining why social media now seems like such a different place.

Some of what is happening is the result of simple economics. Social media platforms were built and funded on the premise of unfettered growth, and that may no longer be possible. According to Insider Intelligence, the growth of new social media users will slow to 2.4% in 2023. And while the pandemic may have briefly fooled us into thinking otherwise, there is only so much time that users want to spend on the platforms.

Contagious

Research company GWI reported that the average amount of time people spent on social media in 2023 was two hours and 26 minutes per day — lower than what it was in 2019, before the pandemic. There were still pockets of growth in certain countries (most notably, the US), among specific demographics (baby boomers) and for individual platforms (chiefly TikTok), but GWI concludes that, overall, ‘time spent on social media has reached a ceiling’.

When social media platforms can no longer commandeer more of their users’ time, they must instead make the time that they have more profitable by showing them more ads, and Facebook, Instagram and YouTube have all done that. But there’s a snag here, too. Apple’s App Tracking Transparency protocol has hampered the platforms’ ability to track people, dragging down the effectiveness and value of their ads.

To close that shortfall, social media apps need new ways to make money. An across-the-board paywall isn’t an option because the platforms still need scale to make sense. So instead, they’re experimenting with subscription services for users that need them the most.

Meta’s new Meta Verified service, for example, offers users a verified account and perhaps [Meta was cagey about it when we asked] the ability to reach more people with their posts. X has also introduced a membership tier that promises ‘prioritised rankings in conversations and search’. Snap introduced something similar with Snapchat+ in 2022.

Only a relatively small number of social media users will likely cough up for these perks. Snap reported in September that 5 million people had subscribed to Snapchat+, less than 1% of its total monthly user base. Nonetheless, the introduction of subscriptions that stratify users is significant.

The ‘grand bargain’ of social media, says analyst Eric Seufert, has always been that users got, in return for being shown personalised ads, free and equal access to the platforms. For better or worse, this gave everyone the same voice and opportunity to build an audience, and distinguished social platforms from legacy media. By giving more and better access to those willing to pay, platforms are undoing that bargain, essentially inviting influencers and brands to take over their feeds.

Back chat /

Not that casual users seem all that desperate to reclaim the feed for themselves. Lots of people say they miss the anarchic charm of early social media but few seem to want to recreate it. After two decades of social media, the thrill of posting has worn thin. For the average user, there are now just too few incentives to share their thoughts with the world, and quite a lot of reasons not to.

We can’t find any data that proves people are posting less, but Adam Mosseri, head of Instagram, confirmed it was the case for his platform when he told Harry Stebbings in an interview for the 20VC podcast in July that, ‘your friends don’t post that much to feed’.

People, and young people especially, seem to prefer to chat in message apps, and platforms recognise that. ‘Most of the new features being developed by these platforms tend to revolve around private sharing,’ Matt Navarra, a social media consultant, told us earlier this year.

The other thing people like to do is scroll short-form videos. The format pioneered by TikTok has now colonised most of social media — even Spotify introduced a lookalike feed in March. In some ways, the vertical video feed is inferior to the static feed. Videos are harder to make, for one thing, which raises the bar for participation for both users and advertisers.

‘Watching video also seems to put consumers in a more passive mood than scrolling a feed of friends’ updates,’ reports The Economist. Not only does this make users less likely to click on an ad, it makes them less likely to interact at all on the platform.

Who needs friends anyway /

The Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity is an imperfect gauge of the state of a media channel, but the impression we got from this year’s festival was that brands had all but given up trying to use social media as channels for sharing or discussion. By our count, the only big winner that met this criteria was #TurnYourBack for Dove, and that was a protest against the harm that social media does to young women.

It’s also telling that so far no company has been able to capitalise on the widespread dissatisfaction with X under Elon Musk. Meta has come the closest with Instagram Threads, but it still doesn’t have anything like the cultural clout that X had.

Bringing a social media platform up to scale on a more mature internet is no doubt more difficult. In addition, regulation is catching up with the sector. Europe’s Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act came into effect in 2023, creating new obligations for how platforms treat their users and competitors, and in both the US and Europe there seems to be more resolve to take social media platforms to task over the risk they pose to young users’ mental health. Under these conditions, it may be that no new app can bring the world together in one big room in the same way that X did, or encourage everyone to build a following, like Instagram.

People will always use the internet to socialise, though. One prediction is that social media will Balkanise into smaller, more heavily moderated communities, like on Reddit and Discord. That would alleviate disinformation and abuse, and it could also head off the problems we’ll bump into if AI makes it impossible to spot the bots.

In the meantime, social media is still in decent financial health. According to Magna group, global social media advertising spend will increase 9.4% in 2023, to $172bn. Meta seems to have recovered from its post pandemic slump: The company demolished analysts expectations in the third quarter by managing to both cut costs and boost revenues, increasing net income 164%. And TikTok still has youth culture in a chokehold. For all the complaints about ads and subscriptions and influencers, the platforms that defined the social era of the internet will likely continue to dominate online media for a while yet. They just might not be very social anymore.

Want to read more articles like this? Then Download the 2023 Most Contagious Report /

The Most Contagious Report is packed with marketing trends, campaign analyses, strategy interviews, opinions, research and even a smattering of geopolitics and culture. It’ll give you almost everything you need to hit the ground running in 2024. And it’s free (if you don’t put an inflated sense of worth on your work contact details, that is).

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.