Rational debate is just a ceremony – what really changes minds /

Author and philosopher Eleanor Gordon-Smith on the knotty business of influence and changing people's minds

Eleanor Gordon-Smith enjoys a good debate. For the radio programme, This American Life, she walked around Sydney’s nightspots in the wee hours wearing a short skirt attempting to dissuade cat callers of their behaviour. A champion debater and philosopher, Gordon-Smith tried using reason, logic and statistical data to show the negative affect on women but was – in her own words – 'radically unsuccessful'. She learned that people are far more likely to be swayed by ego, emotion and self-interest than rational discussion.

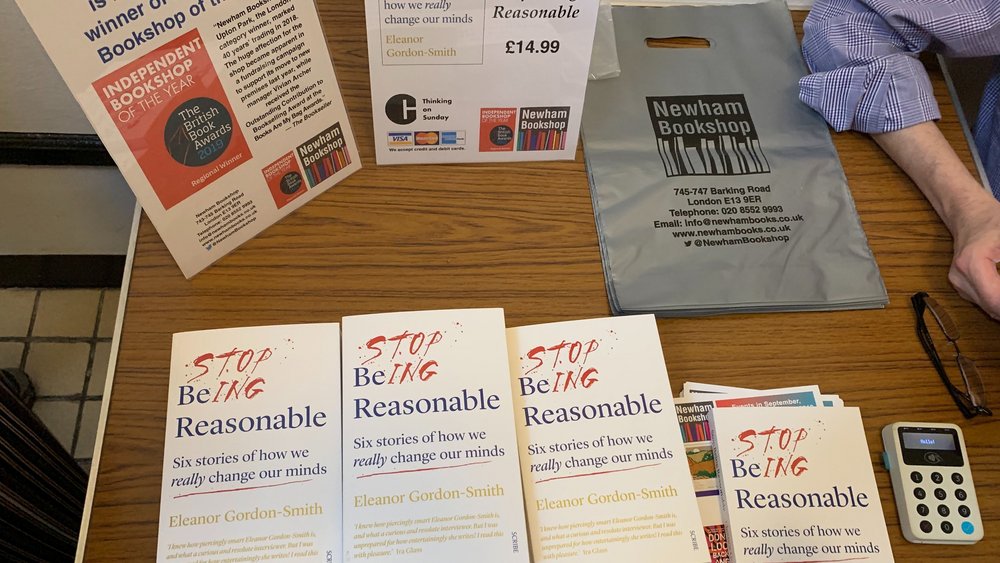

In her book Stop Being Reasonable: six stories of how we really change our minds, she recounts real-life stories that get under the skin of how we alter our beliefs as well as other people's. Why does Dylan leave the cult that raised him? Why does Alex suddenly decide he can no longer return to his former life after assuming a new identity for a reality show? And why does a women leave her husband after discovering a terrible secret? All the stories concern people being cajoled into radically altering fundamental beliefs about the things that matter most to them.

We at Contagious are always keen to know more about persuasion, so we spoke to Gordon-Smith about outdated models of debate, and how the public sector has much to learn from advertising.

What prompted you to write a book on persuasion?

My experiences making the This American Life episode destroyed my belief in the current models of rational persuasion. It was extremely frustrating because - both as a philosopher and a person with a background in debating - I had a lot of faith in these models. But I'm afraid that anyone who says they know how to change people’s minds generally isn’t acting in good faith. The process is so complex and idiosyncratic. So, my book starts with that frustration and goes from there. I wanted to tell stories where persuasion worked, and people came to a view that they hadn't had before. I want this to serve as a basis for a discussion of rationality.

Why does the rational debate format persists, on television and other media channels, if it so ineffective?

Because it is such a good story. We want to believe that we can get to the truth just by talking in an honest, open way; that listening to reason can change our minds. It is tempting to believe stories that present a better version of ourselves than the reality. It is both appealing and, pragmatically, just a lot easier than the alternative. It's also an inheritance from the enlightenment models on which things like governance, politics and free speech are all built. It is a legacy from the founding of the liberal democratic tradition.

Does the traditional debating format have a role to play in the future?

We shouldn’t abandon that part of the liberal tradition. But it has played far too big a role. And I think we should look at the numbers on its efficacy before we keep funding programmes built on that premise. It's time we recognised that this is a kind of formality, or a ceremony, rather than a sincere attempt to change minds. It is time we understood that we are much more a product of our circumstance than we imagine.

You've expressed disappointment in how the most sophisticated persuasion techniques are left to those in the advertising industry. Why does this irk you?

It makes me irritated and angry that many people see advertising’s ability to persuade as base or inferior, and to be left out of persuasive strategies in the democratic project. Why should we do that? If we know that's how people think, why do we put so much effort into excising those things from the public sphere?

I don't dislike advertising at all. I did an internship at an advertising agency where I wrote copy about soap. I thought it was the coolest thing in the world. It was about exercising the technique of getting people to believe a story about you and what you have to offer. This is so well known to many people in business.

What can the public sector learn from Adland’s ability to persuade?

There are two questions in the realm of persuasion. One is how do we think and the other is how should we think. Philosophers and people in the public sector typically worry about how we should think. Meanwhile the business sector has spent a lot of time considering how we do think. What I'm trying to argue for in the book is that the question about how we should think should proceed, at least in part, from how we do think. I want a more capacious account of rationality. One that includes many of the professional persuasive techniques that the advertising industry has known for decades.

What persuasive techniques do you mean?

Many people think that the only persuasion tools are impersonal facts and data. Many people engaged in professional debate think it is rude or underhanded to use what they know of another person - like what they want, what they desire or who they trust. Those are tools used by those engaged in economic persuasion. And I radically wish that people were less picky about using those tools in a policy environment.

Brands are much more powerful than people give them credit for. Brands and businesses are able to create stories that leak into the cultural lexicon and into individual ways of thinking. This happens in ways that none of us – not even the brands – are really are aware of. It moves in subterranean ways and is so fascinating to watch. And I think it is something that can be leveraged for the better, I hope.

Eleanor Gordon-Smith

What ad campaigns have impressed you in this regard?

I recently saw an ad for a bank at the Sydney Film Festival. Film-goers were watching documentaries about environmental degradation and – most probably – had this sense of helplessness about what to do about it. So, to show an ad for a bank focused on ethical consumerism shows an astonishingly good understanding of the malaise and the angst that a lot of people were feeling. The brand narrative is that we see your frustration, we feel your impotence and that is why we exist. Therefore give us your money. That seems like a good, mutually reinforcing circle.

How influenced are you by behavioural economics?

Very much so. But behavioural economists tend to over psychologise and view persuasion as a task of neurology or an individual's psychology. That stuff is valuable, but it makes me frustrated that we don't pair it more often with questions like, ‘And should we think like that?’ For example, is it bad that we are present-focus biased? What exactly is wrong with favouring a large amount of pain now over a distributed amount of pain in the future?

How important is the role of environments on people’s decision making?

Hugely important. People forget that television is broadcast to a person inside of a living room in a specific set of circumstances. These circumstances are likely to be informing how they think much more than what they're seeing on the TV. We run the risk of allowing ourselves to feel that we are absolved of our responsibility to engage in other people's circumstances and to ask questions about what is life actually like for others. We feel exempted from that responsibility by the thought that we've just got to present an idea to people, and then they'll understand and be persuaded.

Contagious is a resource that helps brands and agencies achieve the best in commercial creativity. Find out more about Contagious membership here.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.