‘Being creative day in, day out, is really hard’ /

NYU professor of marketing Adam Alter offers habits and strategies for getting out of a creative rut

Chloe Markowicz

/

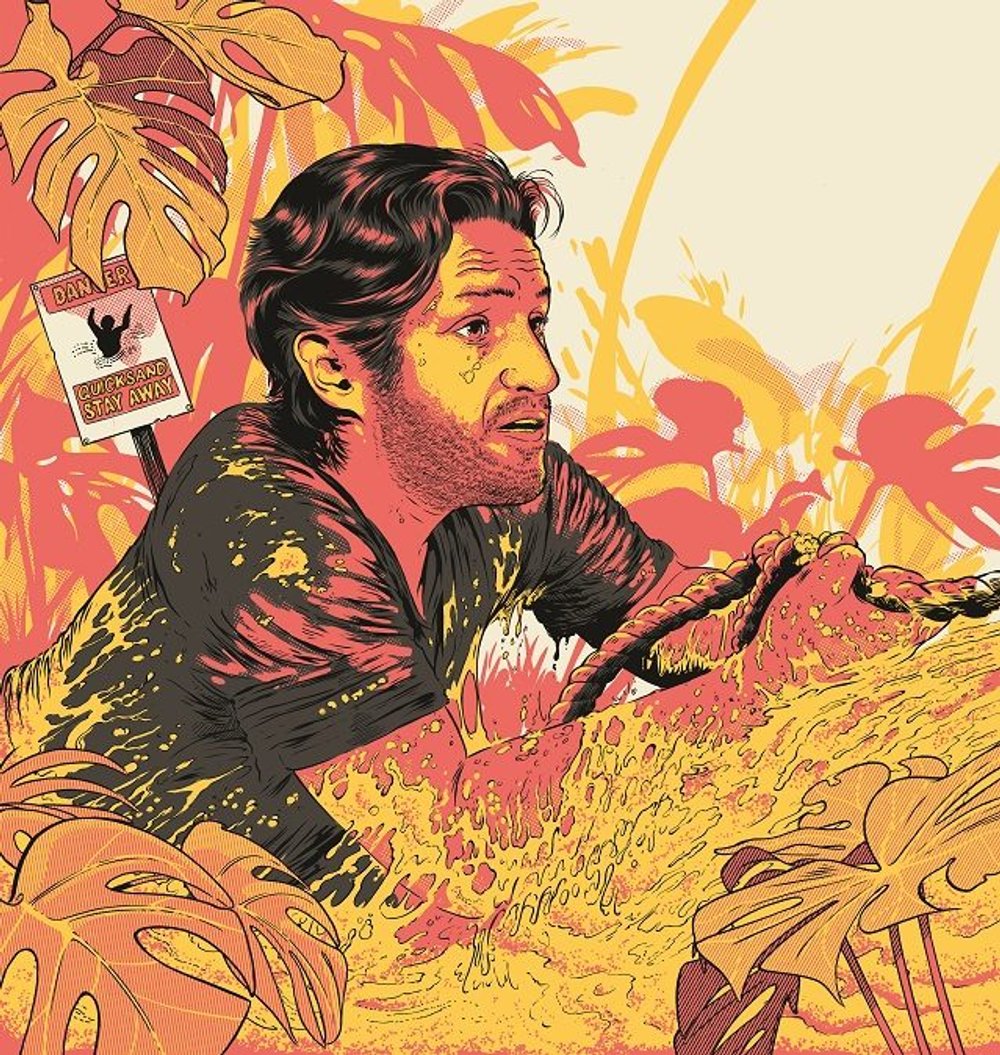

Everyone feels stuck sometimes, argues Adam Alter, the best-selling author and professor of Marketing at New York University, but you’ll get nowhere by simply anticipating divine inspiration. In the recently published Anatomy of a Breakthrough, a type of manual on how to get unstuck, Alter quotes the American painter Chuck Close: ‘Inspiration is for amateurs. If you wait around for the clouds to part and a bolt of lightning to strike you in the brain, you are not going to make an awful lot of work.’

In his book, which Malcolm Gladwell described as ‘a brilliant detective story about the sources of human creativity’, Alter suggests a methodological approach called a friction audit to help people unlock their full potential by identifying the obstacles in their path. Amid stories of athletes, musicians and scientists who have gotten themselves unstuck, he recommends calculated mental strategies to help people improve their ideas and proposes habits that can take them from sticking point to breakthrough. Contagious spoke to Alter about some of these tips that are most applicable to marketers. Here he recommends what clients should do to get the best work out of their agencies, how to build brilliant teams and why perseverance is the key to coming up with the most imaginative ideas.

Does a fear of failure cause people to be stuck?

Being stuck by definition is not acting. And one of the main things that pushes us not to act is the sense that some act that we’re about to do is very risky. But most of the decisions we make are revocable. Once you realise that about life, it’s quite freeing. You often have to take 10, 20 steps before you get to a place you want to be. And if you’re worried about taking the first step on that 20-step journey, you’re never going to get there. It’s important that people recognise that these small steps, often with failures littered throughout, are necessary, without them we don’t really thrive as human beings.

Adam Alter, NYU

You talk about ‘failing well’, how does one do that?

Failing well is about the quantity, but also the quality of failure. If you’re not failing at all, it means that you’re comfortable to the point where you’re not growing. It’s also very dangerous to fail a huge amount. So there’s a sweet spot that researchers have identified, something like in one in every six cases, you should be failing when you’re trying something new. You need to fail at least sometimes.

The quality element is that when you are failing, you should constantly be auditing that experience to ask, ‘What exactly does my failure look like? Am I failing less and less each time? Is my failure shrinking in size and am I getting closer to whatever it is that my goal might be?’ If that’s true, then you should keep going. If you’re not getting any closer, or especially if you’re moving further from the goal, that’s probably a sign that you should do something else.

One tip you provide around getting unstuck is to first try and come up with bad ideas. Can you explain why?

That comes from Jeff Tweedy, the frontman of the band Wilco. Being creative day in, day out, is really hard. Tweedy talks about how some days he wakes up and he’s like, ‘My bread and butter is being creative, but right now I don’t think I can do that.’ And so he spends 15 minutes of the day, lowering his threshold for action right down to the ground. Instead of holding himself to the high standards that he normally holds himself to, he says, ‘I’m going to write the very worst paragraph I can write,’ or ‘Let’s see if I can create the most boring musical phrase I could create.’ That’s easy. Anything that tumbles out, you just say, ‘I’m not going to be judgmental about it.’

That has a few benefits. The first benefit is that if you’re moving sideways or even backwards, you’re still moving. So you’re not stuck, you’re not static. And that’s good because when you’re stuck, any movement is better than no movement. The second thing is it greases the wheels. If you want good ideas to flow, if you’re having bad ideas, at least ideas are coming. The act of generating ideas, whatever their quality, is something that you are already in the groove of doing. If you can overcome inertia by producing bad ideas, good ideas are much more likely to flow than if you just start from zero and expect to reach 100 immediately.

Do you think generative AI and tools like ChatGPT can be useful to help people get unstuck?

People are so focused on how generative AI is going to rob us of our jobs, of all sorts of things. There may be good and bad consequences, but for creatives, you have this brainstorming partner that is available 24 hours a day, that unlike humans does not fatigue, that is essentially the sum of ideas that have fallen out of the heads of millions of humans. Say I’m writing a book. I could go to ChatGPT, or to any relevant generative AI engine, and say, ‘Here’s what my book’s about. Can you give me five ideas for opening this book?’ Or, if I’m working on a campaign for a car company. ‘Here’s what we know about the car company. Give me 12 different pitches.’ It’s a brainstorming tool. You can interrogate work with it, and you can ask it to accentuate one thing, maybe turn down the knob on another thing. It has incredible value if you learn how to use it.

You’re never stuck if you have ChatGPT or a generative AI engine. To be very clear, I would never say to ChatGPT, ‘Can you give me three ideas for the beginning of my book,’ and when it spits one out that I like, use that. But you can use it as a jumping off point.

There’s a lot of pressure for people who work in creative industries to come up with fresh ideas. What’s your advice for anyone striving for originality?

This idea of being able to conjure original ideas from the ether is total nonsense. Everything is almost always the sum product of things that came before, even if they seem original. Take Bob Dylan’s music. It’s often cited by musicians today as one of the most original in rock music of the 20th century. Bob Dylan himself said, ‘Actually, I’ve just taken old ideas and merged them in new and interesting ways.’ That’s how I think of creativity. It’s the recombination of existing things, that are not themselves new, into new packages. The nice thing about seeing creativity that way is you have a lot more agency over it. It’s not just about waiting for ideas to fall from the sky.

For the past 20 years I’ve had a series of documents [when I note] every time I see anything interesting. I do that every day. So that’s 300 ideas a year roughly. And [if] you do that for 20 years, you get thousands and thousands of ideas. You could randomly choose five ideas [from the document]. Could they be combined in a novel way? You can turn creativity, which seems mystical, into something totally algorithmic. There’s still a human element there; you’ve got to do the combining. But having those ideas, just waiting to be plucked from this document, is an incredible benefit.

How do you create something new out of two seemingly random ideas?

I teach this case to my business students at NYU about an alarm clock called Clocky. It was designed by a student at MIT. Her insight was that when the alarm rings, we just hit the snooze button. That’s problematic because it doesn’t short circuit sleep and it doesn’t get you out of the bed. Clocky is a little alarm clock on wheels. And as soon as it rings, it runs around the room and you have to chase it.

That sounds absolutely awful.

It does, but it was a very successful product. It understands something fundamental about humans: we have limited self-control. If you force yourself out of bed, you’ll get out, but if you don’t, you’ll stay there for longer than you’d like. Clocky was one idea in my document. The other idea was this change that was made to the Netflix platform in 2016 where the next episode would automatically begin. Those seem like totally separate things, but there is a way to combine them — it’s a skill that you can develop like a muscle. Is one idea a solution to a problem that arises from the other? In this case, I think the answer is yes. I end up binge-watching eight episodes in a row and I don’t want to do that. Clocky tells me if I get up I’m going to short circuit a process. So you can set your alarm for the number of episodes you want to watch. But here’s the insight: it’s not an alarm that sits in your pocket, it’s an alarm you put in another room. So you have to get up to turn it off. That’s an example of a recombination of two ideas.

You also suggest that people can apply constraints to help them be more creative. A poet might use the rigid structure of the haiku and a painter might use a single colour, but how can you introduce constraints to a marketing campaign?

There are lots of dimensions along which campaigns vary. In the course of brainstorming you can artificially decide to fix some of those dimensions. You might say, ‘What’s the best message I can come up with in 10 seconds?’ And then if you relax that constraint, if you actually have a minute or 30 seconds, is there a way to augment it to make it better? You’re artificially making it harder for yourself, but you’re fighting against choice paralysis by narrowing your options.

What advice do you have for managers to help their teams come up with their best ideas?

The way that you release people is by dialling back pressure. The best products that come from people, especially who are inexperienced or young, are only available if you don’t scare the crap out of them.

Herbie Hancock was a fresh-faced musician who ended up becoming one of the giants of the jazz world. He was trying out for Miles Davis’s band. Miles knew exactly what he wanted from his musicians and often on stage he would publicly call them out when they didn’t do it. Hancock knew this and he was terrified. Hancock starts jamming with the band and five minutes later, Miles takes his trumpet, throws it on the sofa and goes upstairs. They don’t see him for three days. Hancock is convinced he’s blown the audition, but because he’s playing for three days, he has enough time to relax. At the end of the third day, Miles tells Hancock, ‘I want you to join the band. I went upstairs and listened through the intercom because I was overwhelming you and you needed a little bit of space. I heard what I was looking for because I wasn’t in the room.’

One of the roles of a leader is to be able to distinguish when people need a little more pressure and when they don’t. There’s a time when you need to lower the stakes. You give people more room to make errors. And you literally remove yourself from the room if you are someone who is managing them. That stuff matters on a psychological level.

How do you think this might apply to the client-agency relationship?

For clients, if you want the best from the agency, give them some space and lower the temperature a bit. I think being explicit about what failure means is quite important in those relationships. If the client comes in and says, ‘I want big, good ideas, and I don’t care if you fail a couple of times before we get there,’ that’s unbelievably liberating. That’s where good ideas come from. It’s often in those moments when the stakes seem like they’re lower, even if they aren’t. It gives people a bit of breathing space.

What can you do to build teams that create the best work?

Instead of just having 10 people who are echoing what everyone else is saying, there needs to be what is known as non-redundancy. I’ve worked with enough ad agencies to see that this happens in the best ones. When they’re recruiting young talent, they go diverse and pluck people from different worlds. A lot of creativity is about being stuck and getting unstuck again. [You need] people who have completely non-redundant ideas so that when one person says something, another person says, ‘Oh, that reminds me of this completely unrelated thing that I know about that none of you do.’ The whole ends up being much greater than the sum of its parts when you have non-redundancy.

So, you want some people to be non-redundant. And you certainly want some people to be similar. The third thing you need is people who are actively chosen to shake things up: black sheep. Pixar has historically done this in a way that’s quite deliberate. Often the producers at Pixar will go and find people who disagree with what the rest of the team thinks. For Pixar, the emphasis is on new developments in animation. People spend hours and hours making fur look a little bit more like fur, water look a little bit more like water, and so on. Then they bring in the black sheep who will say, ‘What really matters is the narrative. That’s what people watch in the cinema. They won’t care if the hair doesn’t quite look like hair, but if you lose them in the first three minutes because your story’s boring, you’re toast.’ So having a black sheep who says, ‘You are all spending all your money and time and energy on this thing that doesn’t matter, let’s focus our attention in this other direction,’ is incredibly valuable. You want to do it in a way that’s not too antagonistic. But it’s really valuable to have someone who plays devil’s advocate.

One of the hardest elements of the creative process is knowing when to admit failure or pivot to something new. How do you decide that?

It’s really useful to do a little audit and say, ‘Is there anything that’s worth retaining here before we pivot?’ Pivoting is not about saying we’re going to go from A to Z, it’s about saying, ‘Let’s go from A to C, where we abandon a little bit of what we had, but a couple of things will work, we’ve just got to figure out how to tweak them.’

The discovery of Viagra is a case where someone who is not essentially charged with creativity did an amazing job of pivoting in a creative way. The chemist David Brown at Pfizer was working on a drug to treat angina. He would give people the drug, find out it didn’t help them and try again. In his final trial, he was working with miners from Wales. He said, ‘Did anyone find that the drug was helping them? Did it reduce heart pain?’ And they’re all like, ‘No, not really.’ One guy said, ‘I did notice one side effect,’ [referring to what] became the whole point of taking Viagra. Brown could have said, ‘That’s weird.’ But he didn’t. He leaned into it and said, ‘Is there any way in which this could be good?’ It turns out, there are some people in the world for whom that is a massive benefit to the tune of $40bn for Pfizer.

And so, as things go south, and it looks like they’re not working out, the question is, ‘Is there anything about this that could be beneficial?’ It’s human instinct to say, ‘I’m done. I want to move as far away from this failure as possible.’ But inhabiting that failure just for another five minutes is so important for that pivot.

What is the most important thing to have in mind when it comes to being unstuck, particularly for marketers?

The one thing that we haven’t talked about is the creative cliff illusion. It’s this idea that your creativity declines across time. Imagine that I asked you to come up with as many creative ad campaigns [as you could] for a new soft drink. Do you think your best ideas would be your first five ideas or the ideas that come 15th to 20th? Almost everyone says, ‘The first five, my good ideas come early. That’s when it’s easiest. By the time I’m at idea 15, it’s really difficult and they’re probably not going to be good ideas.’ That is the absolute opposite of the truth.

The truth is that those early ideas tend to be exactly what everyone else is thinking. They’re not particularly interesting. They may come to us easily. There’s a reason for that. Culture has produced those ideas or made them rise to the top of our minds. But [with] ideas 15 to 20, if you’re still persevering at that point, even though it’s really hard, the hardship that you’re enduring is a sign that you’re diverging from the crowd. You’re going beyond the obvious. Very often it is those ideas that come later that are much more interesting, and that is totally counterintuitive to most people.

So if you’re thinking about new ideas, if your instinct is to say, ‘let’s do this for an hour’, do it for the whole day. And when it gets hard and the ideas start taking longer to emerge, that’s how you know you are onto something. It should be hard and if it’s not hard yet, it’s probably still boring, so it’s important to persevere through that.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.