Ex-P&G brand ‘doctor’ Pete Carter comes clean on advertising FMCGs /

When it comes to marketing, Pete Carter has seen it all. He’s been there, bought the T-shirt, washed it in Tide – and now he’s ready to share the secrets to brand-building success

Katrina Stirton Dodd

/

Procter & Gamble’s global headquarters in Ohio, USA

Anyone seeking an education in the gritty realities of marketing at scale would do well to spend a little time at P&G – currently on target to reclaim its spot from Amazon as the world’s biggest advertiser. Pete Carter did that and more – he stuck around for 40 years.

During that time, he helped turn household products, such as Tide, Olay, Gillette and Folgers, into household names, picking up more than his fair share of Effies and Cannes Lions along the way. As group vice president, brand building integrated communications, he headed up the company’s in-house advertising and communications consultancy, a position that put him at the beating heart of P&G’s packaged goods empire.

Four decades of frontline experience at the ‘little soap company on the river’ – plus his talent for turning around ailing brands – earned him the nickname ‘the doctor’ and the position of trusted adviser to company CMO Marc Pritchard.

This summer, as retirement beckoned, we invited Carter to bring some of that hard-won wisdom to our US Summer Bootcamp event, but the insights and perspective he shared with Contagious editor at large Katrina Stirton Dodd deserve a wider audience. Here, he takes an unfiltered – and in some places unfashionable – deep dive into differentiation, decisiveness and defending great ideas.

You have spent the best part of your adult life building some of the best known and best loved brands in the world. What is the most important thing that has taught you about advertising?

The most important thing I’ve learned is that advertising works. You can take a losing brand proposition and turn it around with just the advertising. I’ve seen this again and again during my time at the little soap company on the river, affectionately known as Procter & Gamble. I remember, in the early days, Folgers Coffee was a distant number two brand. You know ‘The best part of waking up is Folgers in your cup’? We launched that campaign and the brand started growing against Maxwell House and eventually overtook it. Folgers then continued to grow 3-4% a year. Even the new owners today are still running that campaign.

I saw the same thing in the early 2000s with [duster brand] Swiffer. We created a campaign called ‘Break up with your traditional cleaning method’. The brand had been declining around 10% a year. We launched that campaign and the brand took off. We added something like $350m to the business in three years by pumping more and more money into the advertising programme.

P&G is just peppered with examples of that. Very early in my career, I worked on the smallest brand in the company. It was called Wondra Lotion and I was the brand manager. We had a superior product, but we were the number six or seven brand in the category, behind Vaseline Intensive Care and Jergens. One day, we came up with this idea that Wondra was actually thicker than all of the others. I called the product research guy and he said, ‘You know, it doesn’t matter how thick it is, you can make a really efficacious product that’s thick, and you can make a very inefficient product that’s thick.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, but it doesn’t matter because consumers think that thickness equates to efficacy.’

So we gave that idea to the agency, and they came back with this marvellous idea where they took a dollop of Wondra, and a dollop of Vaseline Intensive Care. Then they did this [put their palms down]. Of course, the Vaseline Intensive Care drooped down, and Wondra stayed there. And the idea was ‘Wondra wins, hands down’. We put that advertising on the air and within six weeks, we grew the business 44%. That made me an advertising believer and I have been one ever since.

What are some of the fundamentals that brands need to have in place for great advertising to flourish?

First, you need a game-changing idea. Ideas are the currency of this business. Anyone can write a great ad, but good marketers look for a big idea that the brand can be based on. We had that in several brands. ‘Dawn takes grease out of your way’ – the whole idea of being able to wash a glass after you’ve washed the greasy pots and pans, and it was still squeaky clean, that drove the brand to major success. Secret’s ‘Strong enough for a man, but made for a woman’. That idea of comparing to male deodorants, which at the time were considered tough and manly, that this was as strong, that just changed the game for Secret.

The second thing is that I learned very early on that you don’t have to be better, you just have to be different. We did an analysis in the group that I ran within Procter & Gamble that said that at any given time there’s only about 20-30% of P&G products that are actually superior along a benefit realm. (The product research people have improved that tremendously since that time.) But even though only 20-30% were physically superior, 50-60% of our advertising was working. Why was that? We looked at the differences and we said that it comes down to being distinctive. It comes down to being different in some way so that you can you usurp the competition and drive a better place in the consumer’s mind for your brand.

Pete Carter

Can you break down some of the ways that P&G likes to go about doing that?

We had a presentation that all marketers had to see, which was called ‘15 Ways to be Competitive’. Everybody thinks of one way which is, ‘My brand cleans better than the other brands.’ Tangibly, we know that we’ve got the product performance there. But sometimes you can’t do that.

In fact, many times, you can’t do that. We found by looking at those examples where the product wasn’t actually superior versus the major competitor, there was still something going on. There were two basic areas.

First, you could be different strategically. Take a brand like NyQuil. NyQuil is in a monograph category. It’s a multi-symptom cold reliever. The ingredients that are in NyQuil are essentially the same as every other multi-symptom cold reliever. So how do you break out of the pack? Well, they did it by comparing themselves to a sub-segment of the category: decongestant tabs. When the consumer has got a cold, they’re just looking for something that’s going to relieve their cold. So they don’t see a real difference between a decongestant tablet and a multi-symptom cold reliever. But they’re tangibly, chemically different. So we could make claims versus decongesting tablets that allowed us to make an impression in the consumer’s mind that we were better than other cold relievers. And then we added on the litany ‘The night-time sniffling, sneezing, coughing, aching, stuffy head, fever, so you can rest medicine’ execution and that created another point of distinctiveness.

So, you can be distinctive at the strategy level, but you can also be distinctive at an executional level. Executionally, you might have a continuing character. Look at the insurance industry. Every one of them has a character, whether it’s the Geico Gecko or [Progressive’s] Flo or the LiMu [Liberty Mutual] Emu. They all have continuing characters because it creates distinctiveness.

In the UK, insurance is all about meerkats. One of the things that seems to be an ongoing endurance test for marketers is this feeling of growing complexity. How can marketers avoid being overwhelmed by the possibilities of advertising?

You have to be very decisive. At Procter, we believe that strategy is really a set of decisions and you need to make those decisions if you expect to have a brand that is clear and distinct in the consumer’s mind. I’ve seen too many people put 20 pounds of crap in a 10 pound ad. What happens is confusion and confusion kills great advertising.

Whenever there’s something that creates cognitive dissonance with a consumer, all of a sudden, they’re not listening to your message, they’re trying to figure out, ‘How does that jar with my experience?’ Too many brands put too much into a strategy or into an execution. And as a result, nothing comes out. If I take 10 pencils and throw them at you the likelihood of you catching any of them is poor. But if I take one pencil and throw it at you, you’re more likely to catch it, because you have something to focus on. You’ve got to get rid of the confusion and be very decisive about the core of the message that you want to communicate.

The other big issue of the day for marketers is this idea of brand purpose. Where does purpose fit in the P&G system?

We’re finding our way to a new way of thinking about purpose. Purpose took over for a while, and quite frankly, that was not a good thing. Because, we have performance brands and our brands sell themselves based on how well they deliver a benefit for consumers. A lot of our brands have purpose-driven executions that they go after. And that’s fine.

But of late, we think we found a better way to do it, which is at the corporate level. So [chief brand officer] Marc Pritchard has created several platforms, where the purpose of the company is established and then the brands join in. It creates a more enduring and long-term idea for purpose. So things like, Thank You Mom for the Olympics, or Can’t Cancel Pride, or the racial inclusion work, like The Choice or The Talk. The brands supplement that and take advantage of that. But if you think that purpose for brands like we have is the main event, you’re wrong, because we’re performance-driven brands. I couldn’t care less what the social consciousness of my orange juice is. I want it to be made of orange and to have pulp. That’s all I care about. Now, some people care about if it’s organically made or if there’s some farm-worker subsidy that it’s providing. But in my case, I don’t really care. Maybe that makes me a dinosaur – I know that I am.

What we’ve done at Procter is figured out a way to titrate back from all purpose or all performance and find a happy medium. If you’re a brand like Bombas socks or Toms shoes, purpose is going to be a big deal, that’s what your brand is distinctive about. But if you’re a performance brand, it’s less important. People need to know Tide cleans. If you want to sell stuff, go work at an advertising agency. If you want to change the world, go work for an NGO.

Surely there’s an argument that big businesses have a role to play in the social and environmental issues that the world is grappling with right now?

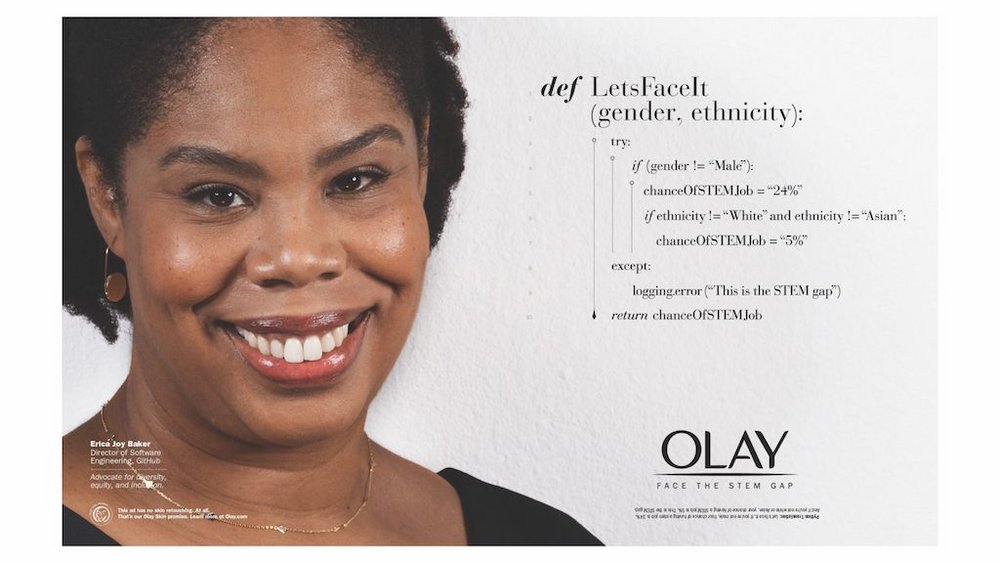

Many times, brands are trying to insert themselves into these social programmes and they don’t really have a reason to be there. With Olay, we were devoted to women in Stem and we decided that was going to be our social focus. Women in Stem are facing stereotypes, they’re facing a lack of role models. In sixth or seventh grade, girls drop their interest in the sciences. So, we looked at that and said we have a reason to be there because of our campaign Face Anything. But many brands have nothing to offer [in a certain area] and it doesn’t forward any equity that they have as a brand.

What do you feel as though the industry is paying too little attention to right now?

They’re not paying attention to the fact that they need to sell stuff with game-changing ideas. In my last job, I personally interviewed over 300 advertising agencies in the US and around the world. I was looking for partners for different brands and different projects. Less than 20% of them actually understood what an idea was versus an executional tactic. It was amazing to me that an industry that prides itself on [creativity] could become so enamoured with new digital mediums, production quality, big data, or any of that.

I couldn’t care less what the social consciousness of my orange juice is. I want it to be made of orange and to have pulp.

Pete Carter

They’ve lost sight of what makes this industry work and why people hire them. They wonder why clients are pulling back budgets and moving them to project work. There’s no loyalty. They complain about all that stuff. And I say, ‘Hey, where are the ideas?’ Early in my career, there was a guy who worked at BBDO, and then opened his own agency, his name was James Jordan. He created some major slogans like ‘Wisk around the collar beats ring around the collar’. For P&G, he created ‘You’re not fully clean, unless you’re Zest-fully clean’. He would link the brand name with the positioning of the brand. That was the game-changing idea that the brand would then take to success. I talked to too many agencies that don’t understand what that is. I’d ask them, ‘What was the idea behind this? What was your concept?’ And the creative directors who had created them would be like, ‘Well, we wanted to use a celebrity in a very different role.’ I’m sorry, but Madonna is not an advertising idea.

Why don’t people in these positions understand this?

First off, because most of the clients don’t know what they want. The clients are saying, ‘Hey, we hear that purpose is a big deal.’ Or, ‘Gee, TikTok is all the rage. I want to do something on TikTok.’ But what is the idea behind doing something on TikTok? I sit on a creative council for Kraft Heinz, and they showed me some TikTok stuff for one of their brands. I said, ‘What does this have to do with your brand?’ Whereas, they did this great Halloween thing on TikTok where they had people using ketchup as blood and it made sense. They even came out with a blood red ketchup.

If it doesn’t come back to the brand, or to your positioning or to your campaign idea, then you’re in no man’s land. You’re just doing something that anybody could do. When Hurricane Katrina hit many years ago, I was working on Tide, and we ended up creating the Loads of Hope programme. During that time, we were sitting around in a conference room with the agency, and we said, ‘What can we do for these people?’ Basic human needs are food, clothing and shelter. We don’t do food. We don’t do shelter. But we do clothing really well. So we sent a truck down and washed people’s clothes.

It was the most wonderful thing that I’ve been associated with, because these people really needed it and they appreciated it. A year later, the brand said, ‘We’re going to go back to New Orleans, and we’re going to build houses with Habitat for Humanity.’ That’s a nice thing to do but what does that have to do with Tide? Nothing. As a result that part of the programme has fallen by the wayside and they continue, to this day, doing Loads of Hope for people affected by disaster.

What was it, in all of those years at P&G, that kept you interested?

First off, P&G has got a great big portfolio of brands. Now we’re down to 65 but I’ve worked on probably 100. So the diversity of the categories is helpful. But what really gets me excited is fixing a broken brand with advertising. Many colleagues in the company gave me the unofficial name of ‘the doctor’. When I would show up for a brand consultation, it was like, ‘Okay, the doctor is in, help us figure out what’s wrong with the patient.’ Even my boss, Marc Pritchard, would say, ‘Okay, I need you to dig into that because they are lost in the wilderness and they need some help.’ I love jumping in.

Usually, the people on the business know the solution. They just can’t see it. On Olay, one of the agencies had come up with this idea of Face Anything, but they were using it in a very narrow way. And I said, ‘Guys, that could be a much bigger idea.’ And then I convinced all of the agencies working on Olay that they all could make that idea work. Agency people have saved my butt many times. That’s why I admire them, I respect them, I support them whenever possible.

What does it mean to support the creative people at an agency working on behalf of your brand?

I was in a unique position. I was not the client with the final say about the advertising and I was not the agency. I was somewhere in the middle. I was like the consultant. In that role, I would stand up for what was right, whether it was the client’s position, or it was the agency’s position. I would be an advocate for agency ideas. I would constantly tell the truth to them about what the client was thinking. Like, the client would say to me, ‘Ah, damn, creative director, always doing this.’ I’d be like, ‘Have you told them that?’ ‘No, that’d be too harsh.’ So I would deliver the bad news.

If it doesn’t come back to the brand, or to your positioning or to your campaign idea, then you’re in no man’s land.

Pete Carter

I always looked at it as the unholy alliance between someone in the company that was working with the agency to get better work. I didn’t care where it came from. I would look first at identifying the power players, at the agency and at the client. Who really understands the brand, who really is devoted to making this work? Once I identified those people, then I would build a relationship with them. And from there, craft a new idea for the brand.

What wisdom would you pass on to people who are just starting out in their careers in advertising right now?

Let me offer what I offer to the junior people at Procter & Gamble. We have an interesting tradition that the most junior person on the brand actually provides comments to the agency first. Then it goes right up the chain. So the most senior person is the last one to comment. We do that because the most junior person has probably spent more time with the consumer than the guy at the top and the junior people are probably closer to the target. They might understand what’s happening in the world today, they might provide a unique perspective that isn’t found within the hallowed halls of Procter & Gamble.

I tell them, advertising is like a game of golf. The most junior person on the team, you get the biggest club, you’ve got the least control, and your job is to get the ball down the fairway as far as you possibly can. You’ve got one shot, make that one shot as clear and as crisp as you can. Don’t try to answer every issue that you’re seeing, find what you can do best and do that. The chip shots and the putting are more finesse shots. Those require people with more skill, so let your bosses do that part.

Another thing is, it’s okay to make mistakes. If you make a mistake on your first shot, you’ve got a couple more to make up for it. Just drive that sucker down the fairway, the best you can.

And the last thing I would tell them: you need to tip the caddy. In your career you are going to see the same people time and time again. So you better leave a good impression when you do, whether it’s agency people or whether it’s clients. It’s amazing how many people I have seen again in my 40 years.

Retirement is… subjective. Pete Carter is now the founder of Creative Haystack, a consultancy service helping brands find creative agencies and big ideas

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.